Rosana Paulino. Amefricana: Exhibition at the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (MALBA)

Author: Andrea Giunta

On March 21, 2024 opens Rosana Paulino’s exhibition at MALBA, Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires. This is her first comprehensive exhibition of her work outside of Brazil, which I am co-curating with Igor Simoes. Active since the 90s, Rosana Paulino – who has been invited to our seminar Narrating Art and Feminisms. Eastern Europe and Latin America – is central to understanding intersectional, black feminism in Brazil and Latin America. Her work enables us to assess how complex and denied themes – such as the consequences of slavery and racial discrimination – intertwine in the narration of modern art in Brazil. It is a story focused on abstraction as a central canon of white Brazilian art. The concept of “racial democracy” has been instrumental in representing the Brazilian case as exceptional, considering it as a country where racism does not exist and one characterized by a harmonious coexistence between the Afro-descendants, indigenous, and white population. This concept is an ideologeme that for decades prevented an open conversation in terms of race, art and discrimination and that involves not only the Afro-descendant population, but also indigenous communities. The policies of occupation of indigenous territories articulated since colonial times remain in force. It was open and internationally denounced with regard to the action taken during government of Jair Bolsonaro. The idea of racial democracy has been stimulated by the interests of the white population, which represents the economically dominant sectors.

Since the end of the 20th century, and increasingly during the 21st century, the history of Brazilian art has begun to be rewritten. First, recognizing and introducing the work of black artists into museum collections (the Pinacoteca de Sao Paulo has been a precursor in this sense); second, founding the Afro-Brazilian Museum in Ibirapuera, in the same park in Sao Paulo where the biennial is held; and third, holding monumental exhibitions such as those presented in recent years by the Pinacoteca, the Sao Paulo Art Museum, the Tomie Ohtake Foundation or the SESC among many others. The curators actively contribute to the recognition and study of the work of Afro-Brazilian artists. These include Emmanuel Araujo, Igor Simoes, Fabiana Lopes, Helio Menezes, Diane Lima, among many others. A field of aesthetic and political interventions has opened an area of urgent research.

What do we know in Argentina about the African presence and the consequences of slavery in Latin America? To what extent do we recognize ourselves in the Latin American racial problem when we feed the perception that our country was populated by Europeans who arrived on ships escaping European famines, poverty, and war between the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century? This perception was also fed by the dominant narrative of the history of Brazilian art made by women artists, strongly linked to the history of this immigration and the relationship with the European avant-garde (Anita Malfatti, Tarsila de Amaral, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Ana María Maiolino, Annabella Geiger, Claudia Andújar, among many other notable artists). Why have there been no great black artists in Brazil when more than 50% of its population is of African descent? These questions are relevant throughout Latin America.

- Rosana Paulino, Parede da memoria (Wall of Memory), 1994-2015. Installation detail. Patuás in acrylic cloth and fabric stitched with cotton thread, photocopy on paper and watercolor, 8 x 8 x 3 cm each piece approximately. Installation dimensions variable. Pinacoteca de São Paulo Collection, donated by Associação Pinacoteca Arte e Cultura, APAC, in 2018 © Rosana Paulino.

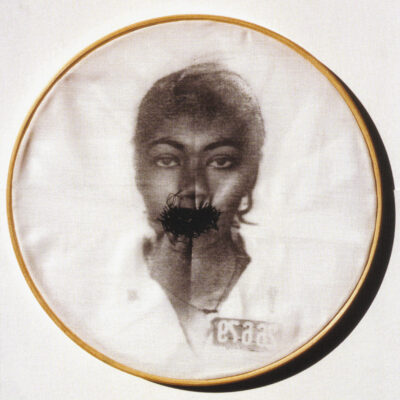

- Rosana Paulino, Sin Título (Bastidores) (No Title) (Embrodery Hoop), 1997, Museu de Arte Moderno, Sao Paulo 30 cm. diameter. © Rosana Paulino.

- Rosana Paulino, Assentamento (Settlement), 2013. Installation view, MAC, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de la Ciudad de Americana, São Paulo 2013 © Rosana Paulino.

- Rosana Paulino, Guará-vermelho (Guará-red), 2023, graphite, acrylic and natural pigment on canvas, 207 x 261 cm. © Rosana Paulino.

The presentation of Rosana Paulino’s subtle and powerful work at the MALBA interrogates, like a boomerang, the construction of the history of Argentine art, where although the presence of a black population has been recorded since colonial times, it has been consistently denied. Only recently have studies been undertaken that review the representations of the black population in the 19th century (like María Lourdes Ghioldi’s book, Estereotipos en negro. Representaciones y autorepresentaciones de los afroporteños en el siglo XIX (Stereotypes in black. Representations and visual self-representations of Afroporteños in the 19th century) published in Buenos Aires by Prohistoria, in 2016). The exhibition also interrogates the MALBA collection, in which Latin American art is approached from the predominant white canon. The black presence is represented by very few artists, among whom Sonia Gomes, Wifredo Lam, Aline Motta and Rosana Paulino herself stand out.

The exhibition Rosana Paulino. Amefricana – a key word introduced by Brazilian philosopher Lélia Gonzalez to name black people from the entire continent, not just North America – includes works between 1994, when she began her Parede da memoria (image 1), and 2024, when she created Geometria à Brasileira, the work that chronologically closes the exhibition. Rosana’s work introduces us to the social place of the black woman (Bastidores) (image 2), the stories that involve her, personally, like the portraits of her family (Parede da memoria). The works to be exhibited address the history of slavery, with some phenotypic photos that the Swiss photographer Auguste Stahl took in the 19th century, of black women and men from the front, from the back and in profile, images that Paulino transposes onto canvas, cuts, and sutures, to account for two processes (image 3). Firstly, the rupture of their lives and their subjectivities caused by capture, transfer on ships, in inhumane conditions, and subjection to slavery. But at the same time the reconstruction that they carry out in Brazil, as subjects with new emotional ties, and various forms of rooting.

Rosana Paulino’s work is a profound call to make visible sensibilities, stories, affections, family ties, thoughts, full subjects whose existence, history, and the history of Brazilian art have been made invisible and erased. This full, sensitive presence, which integrates the human and nature, takes center stage in her most recent paintings, exhibited at the recent São Paulo Biennial in 2023 (image 4). These paintings implied a statement about the forms of representation of the humans and nature – a relationship that feminism had already pointed out in the seventies, during its second wave (then called ecofeminism). The current debate about the Anthropocene—about the place of humans in the context of the environmental crisis and the gradual impossibility of life (human, animal, plant) on an exhausted planet—is part of the most contemporary agenda of feminism. Rosana Paulino points out the different representations of the world that religions offer: while in Catholicism the world was given to humans, in Afro-Latin American religions humans coexist with nature in a non-hierarchical relationship.

What this exhibition is going to introduce into the debate about art in Argentina, I imagine, is the central question about how we have constructed our own history and how the history of art in Latin America has been created. It also raises a powerful question about diaspora studies, led by the Anglophone area, in which Brazil has not been incorporated consistently. This is a history of slavery, denied, relativized, whose contemporary consequences are still present in the existing social inequality. In Brazil, as in other countries in America and on other continents, racism, which has been relativized, exists.

Rosana Paulino’s work presents a double aspect. On the one hand, it shows the extent to which images have been powerful in representing the dehumanization that slavery and racial mixing involved. And at the same time, she elaborates extraordinarily subtle poetics, in which the drawing, the sewing, the fabric, the transparencies of the colors, evoke a sensitive and deeply conceptual imaginary at the same time.

The presentation of this exhibition in Argentina will provoke a debate and endless questions that will prompt us to discuss an aesthetic agenda that until now has not been addressed.