A discreet disagreement with the concept of motherhood

Author: Eda Tuulberg

The following post[1] is a brief analysis of Estonian artist Silvi Liiva’s[2] 1977 etching Põld-Põlluke [Field, Little Field] which I saw during one studio visit. In many ways, this is an exceptional work in the context of the representation of motherhood in late Soviet Estonian art. As a background story, Liiva mentioned that the Ministry of Culture was initially supposed to buy the work, but at the meeting of the purchasing committee, one of the members, an esteemed male graphic artist, quite unexpectedly objected to the purchase of this etching, claiming that the work was not technically perfect; part of the abdomen was not well executed, in the sense that it had been over-etched. Of course, there could have been other reasons why the the work was not purchased, but this is how the decision was justified to the artist, and this is how the author remembers the cancellation of the purchase.

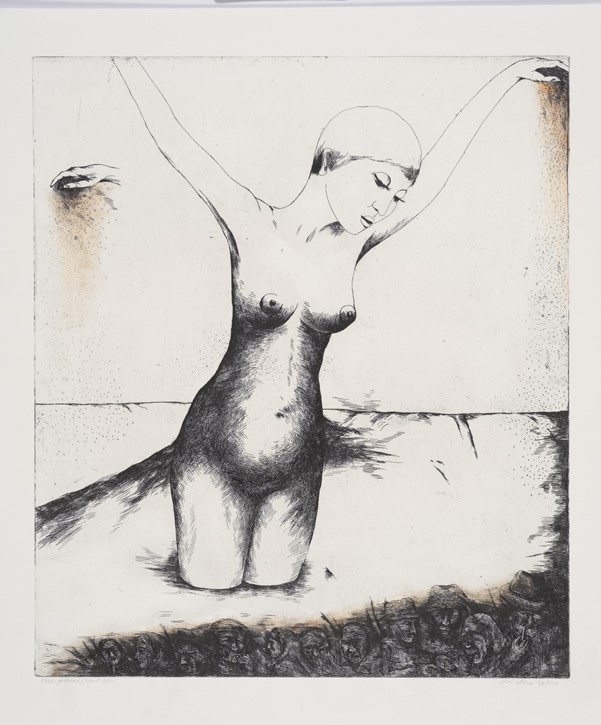

Silvi Liiva. Field, Little Field. 1977. Etching. Courtesy of the artist

However, the intrigue of the story lies in the fact that Liiva depicts a woman’s early pregnancy in the etching, which is why the belly is highlighted and darkly depicted. In addition, today’s viewer will not miss the fact that Liiva’s work is exceptional in many ways as a representation of a pregnant woman, as the naked woman with her short hairstyle looks very modern, even sensual, hence very different from how mothers or motherhood in general was depicted at the time. In the darker lower part of the picture plane, where the woman’s gloomy gaze is directed, the artist depicted people of different ages, mainly very serious elderly looking men and women, whose eyes reflect dissatisfaction. But with whom or what are they dissatisfied? Is it with this young sensual pregnant woman, who symbolically sows grain in the field, but does so in a moody and absent manner, and who does not seem to play her role particularly convincingly or enthusiastically?

Having studied discourse on femininity in 1970s Estonian art criticism, as well as in society in general, it can be argued that motherhood is one of the central aspects associated with femininity and being a woman[3]. Official ideology and the state’s views on emancipation and women’s social equality in the 1970s are eloquently conveyed by the texts dedicated to women published in newspapers on March 8, or International Women’s Day, as part of the International Women’s Year (1975), whether they are “congratulations to women” or, for example, interviews with socially active women who are also successfully fulfilling their motherly duties. From there, on the one hand, the point of view emerges that women have, and should ideally have, equal opportunities for self-actualization in various fields of profession[4]. On the other hand, the rhetoric of equality mostly instrumentalizes women as citizens, values them primarily as builders of communist society.[5] In other words, we see two main vectors in the official rhetoric – the construction of the state and its maintenance. It is in terms of building and maintaining the state that the important role of a woman is emphasized as one of heroic mother[6], who in some cases, in addition to raising six children[7], is also a good and, above all, self-demanding worker. This in turn means that in the eyes of the state and society, the main role of a parent is still played by a woman as a mother[8]. At the same time, women are given the responsibility for the (emotional) well-being of the whole family.[9] Although 1974 documentary Naine täna [A Woman Today] was directed by a women – Reet Kasesalu – and presented the idea that a woman can work in any field that she desires[10], the film begins and ends with a maternity hospital scene, which gives the impression that the symbolic framing of a woman is still as a mother. However, it is telling that in the documentary social scientist Klara Hallik critically stated that women’s mental abilities are not inferior to men’s, but society does not offer any sufficient support structure for women’s self-actualization. Since women have less time away from the family, their access to, for example, the “higher spheres” of science, which requires the availability of time resources, is limited.

What is more, sociologist Ene Hion, for example, wrote critically on March 7, 1975, that the notions of femininity and masculinity are inadequate because “the concepts ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ are social and their content depends on the society in which we live, the era, the norms and traditions of relationships.”[11] At the same time, although we can see that the gender discourse accommodated other points of view, the way of thinking based on biological determinism is most prominent in the case of femininity.

Marju Mutsu. Madonna with Child. 1977. Etching. Art Museum of Estonia

In the context of art, however, an eloquent article on the topic of femininity and motherhood can be found from 1988. It comes from the collection of articles published by the Art History Department of the Academy of Sciences of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic Institute of History entitled New Generations. Maarja Kross’s text offers an essentialist view of the role of a female artist, primarily as a mother and then as a creator. The text draws a clear and rigid line between women and men, treating them based on a binary gender model. The author expresses the idea that femininity is something specific to a woman, and a woman’s main goal in life and society is to be a mother. According to this text, which appeared in a collection of articles dedicated to young artists, a woman can of course be an artist, but the author emphasizes that it is difficult to be a female artist when you have to take care of home and family at the same time. However, in the opinion of the author of this text, not being a mother is something unnatural for a woman, because “nature in a woman knows exactly what she needs.”[12] First, we see the same pattern here, that taking care of children is primarily a woman’s responsibility. Against the background of this text, it is also worth mentioning that, just as the work of male artists was not associated with the specifically masculine element expressed in their works, the interviews of male artists also mostly did not talk about family life, while in the context of women, the question of the mother’s role and how to cope with different roles was present. Silvi Liiva honestly emphasized in the context of motherhood that the most important thing for her when she came to the city from countryside to study, was to get an education and the opportunity to fulfill herself as an artist.[13]

So, examining the discourses, it emerges that although female artists are considered – and they consider themselves – equal to their male colleagues, in the context of most artists or creative individuals, raising children was considered primarily a woman’s role, or even if it was not formulated in that way, the real situation turned out to be like this.[14] The role of a mother may not necessarily have been more important than being an artist for the women themselves, but in many cases the role of a mother or wife in general began to influence their lives and choices. It also seems that being a parent influenced female artists significantly more than male artists. In fact, I have not yet heard any male artist claim that his work and creative choices, decisions, or opportunities are or have been limited by being a man.

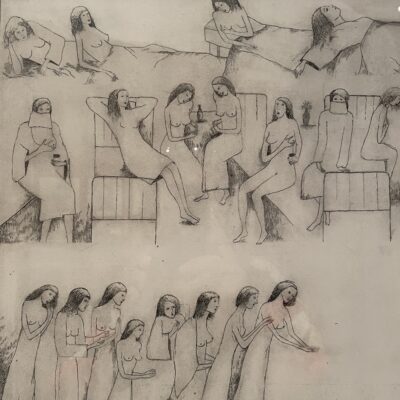

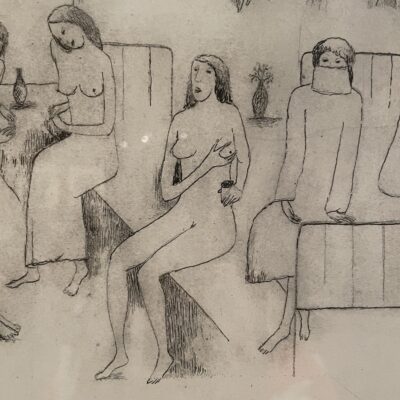

If we look women printmakers of that time period, it can be argued that their representation of women differed in many ways from the concepts of femininity and motherhood prevalent in both official rhetoric and art discourses. I would suggest they offered a different way of interpretation and viewing, which does not reflect (only) stereotypical femininity. Silvi Liiva’s etching Field, Little Field is a great illustration of it. The depicted female nude in Liiva’s work is symbolically connected to fertility and earth, but the image has a feel of melancholy. Although it is not possible to unequivocally state that the work consciously and straightforwardly problematizes the essentialist approach to gender (even the author herself tends to reject this interpretation nowadays), this representation of a pregnant woman seems ambiguous and intriguing, especially taking into account the above-mentioned discourse. It is not a depiction of heroic motherhood, but quite the opposite. The woman seems absent and, one could say, burdened by something. The woman’s lowered gaze and physically exhausting pose add psychological tension to the work and contribute to the somewhat gloomy atmosphere. It seems that the figure is tired and is about to collapse on its side in the same field. As mentioned previously, in the case of this work, there is some dissonance between the traditional image of motherhood and the modern, sensual image of a woman depicted by Liiva in the considered period, as the image of the pregnant woman depicted in the work is quite exceptional. I have not accounted a representation of a young, modern, sensual mother or a pregnant woman before. In the case of Silvi Liiva there is also a rather non-heroic and humorous work entitled Suvi. Sünnitusmajas [Summer. In a Maternity Ward] from 1973, which is also an unconventional way of mediating the experience of motherhood, especially in the context of the official imagery and ideology of the late Soviet period. From Marju Mutsu’s oeuvre, we could highlight Madonna lapsega [Madonna with Child] from 1977, which also visualizes and signals rather psychologically complex and ambivalent shades of the experience of motherhood.

- Silvi Liiva. Summer. In a Maternity Ward. 1973. Etching. Courtesy of the artist

- Silvi Liiva. Summer. In a Maternity Ward. 1973. Etching. Courtesy of the artist. Detail

- Silvi Liiva. Summer. In a Maternity Ward. 1973. Etching. Courtesy of the artist. Detail

So, to conclude, although not straightforwardly criticizing the existent gender norms and dynamics of late Soviet period, I would like to state that Liiva did not depict or mediate the contemporary social image of a woman or the narrow notion of femininity at the time, but offered a discreet disagreement with the concept of motherhood and hence contributed to broadening the human experience.

[1] The text is partly based on an article published this year in Estonian entitled Kõht on ülesöövitatud, ehk kitsendatud “naiselikkus” [The Abdomen is Over-Etched: Constructed Femininity].

[2] Additional information regarding Liiva could be read here: https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/silvi-liiva/

[3]´Femininity. Is it changing or disappearing? Many attempts have been made to define femininity, but it is one of those concepts that is very difficult to express in words. In no way does femininity mean special weakness (cowardice) or lack of some quality (incompetence). Quite the opposite! Femininity is about having something. Femininity comes out better in the role of mother. The terms woman – femininity – mother are inextricably linked.” Interview with Professor Kadri Gross of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. TRÜ: Tartu Riiklik Ülikool: EKP TRÜ komitee, TRÜ rektoraadi, ELKNÜ TRÜ komitee ja TRÜ ametiühingukomitee häälekandja, 15.10.1982.

[4] For Soviet Women. – Rahva Hääl, 08.03.1975.

[5] International Women’s Year. – Kodumaa, 08.03.1975.

[6] H. Taliste, Woman and politics. Conversation with revolution veteran Alma Vaarman. – Kodumaa, 08.03.1975. Of course, it must be stated that this was official Soviet rhetoric, with which the Estonian intelligentsia, including the artistic community, apparently to a large extent did not agree.

[7] Kodumaa, 08.03.1975.

[8] In 1975, Armilda Jürimäel, the chairman of the Estonian Republican Committee of the Cultural Workers’ Trade Union, commenting on the situation of women’s issues in Soviet Estonia, emphasizes (rather seeing it as a woman’s advantage) that legislation favors women in matters of child care. See the interview with Armilda Jürimäel, the chairman of the Estonian Republican Committee of the Cultural Workers’ Trade Union. – Kodumaa, 08.03.1975.

[9] See, for example: For Soviet Women. – Rahva Hääl, 08.03.1975; S. Kuulpak, International Women’s Day is a political holiday: several possible ways of being a woman. – Kodumaa, 07.03.1984.

[10] “Women are allowed to do everything. To learn? Please, study if you like. To work? Please, work as you wish. To be beautiful? Please. Be if you can. To create beauty? Why not. A woman can do anything.” A Woman Today. Director Reet Kasesalu, Tallinnfilm, 1974.

[11] E. Hion, Man and Woman. – Sirp ja Vasar, 07.03.1975. In this article, Hion critically points out the problem that men’s responsibility for family life has decreased. She writes that the earlier conception of femininity highlighted “… indulgence, softness, passivity. The idea that the right woman knows from the first hint when it is necessary to hand a man a pipe and when slippers, has remained from the past. Feminine has also meant a not very great mind”. She is critical of this entire symbolic order, stating that “in the case of that former feminine woman, the responsibility for the family was on the man. Now a large part of the responsibility has fallen on the woman’s shoulders. The woman’s masculine exterior probably reflects the new balance of forces. Even the woman understands that the man’s burden of responsibility has become somewhat lighter. To whom it benefits?’

[12] M. Kross, New Generations. – Artiklite kogumik, 1. vihik. Tallinn: ENSV TA Ajaloo Instituudi kunstiajaloo sektor, 1988, lk 108–118.

[13] At the same time, Liiva emphasized that she had to give up teaching at some point, because “it was difficult to serve the three gods (home, school and work)”. Conversation with Silvi Liiva.

[14] Of course, it must be mentioned that there were of course also exceptions. The painter and interior architect Mari Kurismaa mentioned in an interview that her marriage with the artist Kaarel Kurismaa functioned on a fairly equal basis. Housework and taking care of the children were divided between the partners in such a way that both could also apply themselves professionally. Interview with Mari Kurismaa, 28.08.2020. Recording in the possession of the author.