A reflection on Las olas del deseo. Feminismos, diversidades y cultura visual 2010–2020+

Las olas del deseo. Feminismos, diversidades y cultura visual 2010–2020+

Casa Nacional del Bicentenario

March 11–September 11, 2022

- Diana Dowek, Mujeres queridas, series, 2014-2021. Mixed media on canvas.

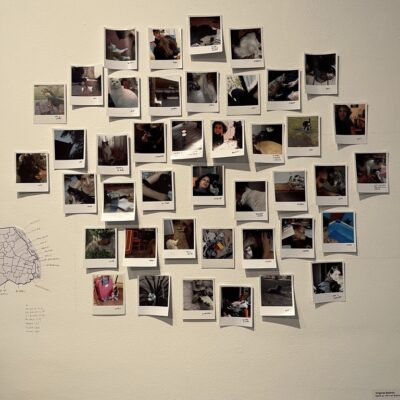

- Virginia Buitrón, Nómade urbana (installation detail), 2015/2022. Paper, photos, condiments, clothing, backpack.

- Leticia Obeid, Así lo hago yo (installation view), 2017. Video (duration 16 minutes, 52 seconds).

In her book, Feminist International: How to Change Everything, political scientist Verónica Gago argues for embracing the concept of feminist potencia. She contends that this act “is to vindicate the indeterminacy of what one can do, of what we can do—to acknowledge that we do not know what we’re capable of until we experience the displacement of the limits that we’ve been made to believe and obey.”[1] This is anything but an abstract concept, according to Gago. Instead, “feminist potencia is desiring capacity.” She explains, ”This implies that desire is not the opposite of the possible, but rather the force that drives what is perceived as possible, collectively and in each body.” Desire, that is, can change everything.

Accordingly, desire takes center stage in the exhibition Las olas del deseo. Feminismos, diversidad y cultura visual 2010–2020+ [The Waves of Desire: Feminisms, Diversity, and Visual Culture 2010–2020+]. On view at the Casa Nacional del Bicentenario in Buenos Aires from March 11 to September 11, 2022, the show briefly addresses desire in its curatorial text:

This exhibition projects toward the future

through the making of the artists

and the collectives convened,

imagining new possible worlds,

advancing toward the conquest of the desired

with the fury and calm of the tides.[2]

The concept of a conquered desire remains opaque in this poetic introduction. Nevertheless, it prioritizes the potentiality of finding other possibilities for life, a theme that emerges throughout the artworks on view. Occupying two floors and a section of the entryway of the Casa Nacional del Bicentenario, Las olas del deseo includes photographs, installations, paintings, and videos by more than eighty artists and collectives from Argentina.[3] As a way to position itself historically, it asserts that it builds on the exhibition Mujeres 1810–2010 [Women 1810–2010], the inaugural exhibition of the Casa Bicentenario in 2010. Twelve sections and a site-specific installation on the ground floor divide the show. On the first floor, Mural de activismos [Wall of Activisms]; Marchar, ocupar, manifestar [March, Occupy, Protest]; El propio cuerpo es acción [The Body Itself is Action]; Coser, tejer, bordar [Sew, Weave, Embroider]; Revisar la/s historia/s [Looking Over History/ies]. On the second, Cuerpxs y placeres [Bodies and Pleasures]; Familia, amor, amistad [Family, Love, Friendship]; Vida doméstica y tareas de cuidado [Domestic Life and Labors of Care]; El arte como trabajo [Art as Work]; Comunidades [Communities]; Pensar el sistema [Thinking the System]. The gallery space also includes a library section with critical books, journals, and magazines related directly and peripherally to the topic of feminism. Additionally, the show’s scope supersedes the Casa Nacional del Bicentenario, moving into the digital sphere with Inmersión – Archivo de archivos. The immersive online platform provides information and links to exhibitions, editorials, activisms, debates, and archives that concretize new paths for an investigation into the histories and presents of womxn.

Las olas del deseo builds on the recent surge of the Ni Una Menos movement, which takes its name from the phrase often heard at demonstrations, “Ni una mujer menos, ni una muerta más.”[4] It formed in 2015 following the death of 14-year-old Argentine Chiara Páez, who was murdered in the act of intimate partner violence when her boyfriend discovered she was pregnant.[5] In response, on June 3 of that year, the first demonstration of the Ni Una Menos movement took place. Since then, the collective has organized annual and intermittent mass demonstrations.[6] While the full force of Ni Una Menos has developed within a relatively rapid period, it comes from a long line of women’s rights movements in the South American nation. These include Encuentros Nacionales de Mujeres [National Meeting of Women], Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal, Seguro y Gratuito [National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion], from the efforts of the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo [Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo], and the extensive acts of the LGBTIQ+ community.[7] Due to the long-term activities of these numerous collectives and others, Argentina legalized abortion on December 30, 2020.[8]

With so many of these monumental events taking place within the time frame of Las olas del deseo (2010–2020+), the exhibition poses the opportunity to ask the following question: How to represent a movement in process, one that is developing daily in the public sphere? Art exhibitions, in particular, have the power to inscribe a specific perspective into history. The curatorial collective of Las olas del deseo productively complicates this problem by addressing an immense range of issues that intersect with the concerns of Ni Una Menos and what might be called fourth-wave feminism in Argentina: intimate-partner violence, gender-based violence, the right to abortion, and new forms of neoliberal exploitation, to name just a few examples. This acknowledgment of the different challenges that women face given race, class, gender identity, sexuality, age, and economic income reveals the developments of the feminist movement since the first International Women’s Year in Mexico in 1975 when tensions boiled due to the prioritization of white, European, middle and upper-class feminism over the concerns of Indigenous women.[9] The challenge for the curators of Las olas del deseo is how to cohesively communicate such diversity of perspectives without proposing finite conclusions.

The exhibition’s real accomplishment emerges from its combination of references to the political movements of recent years alongside artworks that flourish on their own timeframes, agendas, and interactions. In this sense, Las olas del deseo affirms that the efforts of Ni Una Menos unfold in the aesthetic realm on the scale of the micropolitical, following political philosopher Suely Rolnik. Rolnik advocates for more consideration of the microsphere in contemporary politics, “the sphere of unconscious formations in the social field.”[10] Her argument articulates the continued subjugation of oppressed communities through the left’s focus on inclusion, which positions the capitalist colonial realm as the sole reference for vitality and, as such, denies alterity. This process, Rolnik concludes, can be summarized as such: “In short, what is ignored and neutralized is [the oppressed’s] strength for micropolitical resistance.”[11]

These forms of micropolitical resistance are evident in several works throughout Las olas del deseo, particularly by artists such as Diana Dowek, Leticia Obeid, Virginia Buitrón, and the collective Comedor Gourmet. With these, we see that insurgency occurs not through distinct actions of empowerment but through the potentialization of life. Concerning this topic, Rolnik writes,

Differentiating potentialization and empowerment is especially indispensable for bodies considered of less value in the social imaginary—bodies of women, homosexuals, transsexuals, transgender people, black people, indigenous people, the poor, precarious workers, refugees, etc. When their insurrection embraces potentialization and refuses to restrict itself to the claim of empowerment, it is more likely that the drive’s movement will find its utterance and from it an effective transmutation of individual and collective reality will result.[12]

Dowek, Obeid, Buitrón, and Comedor Gourmet communicate a perspective that refrains from speaking the same language as the institutions that oppress them. One of the most stunning in the show, Diana Dowek’s Mujeres queridas [Beloved Women] (2014–2021) is a series of mixed media on large-scale canvas portraits of prominent female figures such as Virginia Woolf, Marie Curie, Simon de Beauvoir, Aída Carballo, and a Madre de la Plaza de Mayo.[13] These depictions are a tribute to the contributions of women that cross disciplines, space, and time. Affirmations of women’s lives and achievements in the face of oppression, the portraits are different character studies focusing on the intricacies of facial expressions and body postures. Rather than heroized by their medical coats, medals, books, or other accouterments for which they are so often known, they are depicted unadorned. Their existence is enough to affirm their right to representation.

Portraiture is reimagined as a form of documentation in Virginia Buitrón’s Nómade urbana [Urban Nomad] (2015/2022), an installation composed of polaroids that the artist took of herself, maps, and even cooking spices from her years of leading a nomadic life. From 2015 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020, Buitrón rid herself of her assets to live in the houses of friends, colleagues, and strangers who opened their homes to her. Renouncing the traditional vision of the nuclear family stationed among their possessions, Nómade urbana speaks to a method of inhabiting that relies on reciprocity and friendship, elements that deny a capitalist market. This other possible world that Buitrón desires can be considered a form of micropolitical resistance, a rejection of the mode of living dominant society imposes on women and individuals who do not ascribe to the heteronormative behavior.

In Rolnik’s formulation of the micropolitical, she asserts that agents must be composed of the human and the nonhuman. Leticia Obeid’s Así lo hago yo [I do it this way] (2017) brings the species together through filming the astute observations made by the human and late writer, Hebe Uhart.[14] A sixteen-minute video, Así lo hago yo features Uhart in conversation with her editor Andrea López as the two peruse a bio park in Temaikén, outside of Buenos Aires.[15] At the time, Uhart was in the middle of writing what would be her final book, Animales [Animals]. An observation of the other-than-human beings with whom humans share the planet, the book reorders hierarchical classification, redirecting attention away from the Western Nature/Culture divide that prioritizes humans above all else. Capturing Uhart’s creative process, Obeid also invests time in the intersections between the species while lingering her camera on the birds, mammals, and other creatures in cages. In the context of Las olas del deseo, Así lo hago yo creates space for a dialogue around the intertwined oppression of nonhumans and women.

- Wall dedicated to the collective Comedor Gourmet in Las olas del deseo.

- Florencia Böhtlingk, Pañuelazo en el Congreso, 2019. Oil and acrylic on canvas.

Carrying questions of feminism and ecology into the realm of health and the body, the collective Comedor Gourmet dedicates its work to providing healthy and delicious meals to areas with little economic means. As the presentation of their work in Las olas del deseo displays, the members of the collective contend that food should be just as much about pleasure as survival, even for those without money to spare. In this sense, their project deconstructs the very idea of what it means to be poor. “El placer es un derecho de todxs,” the group proclaims in their exhibition presentation.[16] Formulating pleasure into a sensation experienced by individuals of all economic backgrounds, the collective’s work raises the same question of desire that structures the exhibitions. They ask, in a capitalist colonial society, who is allowed to desire? In this sense, the act of pleasure in the context of sustenance is positioned as a micropolitical act.

These interventions by Dowek, Buitrón, Obeid, and Comedor Gourmet are interspersed with other artworks, archival materials, and histories that refer directly to the demonstrations of Ni Una Menos and its related actions. On one wall, all the names of those who signed the Nosotras Proponemos statement in 2018 scroll slowly, visualizing the extensive support for fair and just treatment of women in the arts.[17] In another room, a Wall of Activisms traces the numerous demonstrations and support for the feminist movement with historical facts and photographs. Nearby, Florencia Bӧhtlingk’s beautifully haphazard oil and acrylic on canvas, Pañuelazo en el Congreso [Pañuelazo in the Congress] (2019), overlays scenes of Buenos Aires with a variety of political phrases and chants related to Ni Una Menos, such as “Sobrevivir un aborto es un privilegio de clase” [Suriving an abortion is class privilege] and “Budin Vegano” [Vegan Pudding], referring to the growing support for veganism amongst the feminist community.[18] Rather than denying the subjectivities of individuals, these works reaffirm the potentiality of micro-actions. It shows how the mass demonstrations we see in the street flourish and arise from the discrete actions of individuals in their daily lives, reaffirming their subjectivity, worldviews, and right to pleasure, joy, and desire. Ultimately, the Ni Una Menos Movement attempts to address the right that oppressed humans have for life. Whether or not it achieves such a goal is to be seen, but what Las olas del deseo reveals is the many ways citizens can exercise such desire.

By: Madeline Murphy Turner

[1] Verónica Gago, Feminist International: How to Change Everything, Liz Mason-Deese, translator (Verso Books, 2020).

[2] Esta exposición se proyecta hacia el futuro,

a través del hacer de los y las artistas

y las colectivas convocadas/os,

imaginando nuevos mundos posibles,

avanzando hacia la conquista de lo deseado

con la furia y la calma de las mareas. (translation mine)

[3] The exhibition is collaborative and multifaceted in nature. The large curatorial team is composed of a number of scholars: Valeria González, María Isabel Baldasarre, Viviana Usubiaga, Jimena Ferreiro, Luciana Delfabro, María Fukelman, Marcela Roberts, Georgina Gluzman, Cecilia Palmeiro, Nancy Rojas, Julia Rosemberg, and Eva Grinstein.

[4] The phrase comes from the feminist Mexican activist Susana Chávez, who was assassinated in 2011. Patricia Sánchez Aramburu, “La potencia feminista de Véronica Gago y el pensar situado desde una huelga de mujeres,” Debate Feminista 63 (January 2022): 190. “Not one woman less, nor one more death.” translation mine.

[5] Paulina Cohen, “Not One Woman Less: An Analysis of the Advocacy and Activism of Argentina’s Ni Una Menos Movement,” UCLA Women’s Law Journal 29.1 (Summer 2022): 114.

[6] For example, on June 27, 2022, Ni Una Menos organized a demonstration outside of the U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to abortion. This act demonstrates that Ni Una Menos’s concerns extend to the international rights of women.

[7] Sánchez Aramburu.

[8] Although the law (which allows the termination of a pregnancy within the first 14 weeks) went into effect in January 2021, many doctors throughout the country still refuse to perform the procedure.

[9] For further reading on the 1975 International Women’s Year, see Jocelyn Olcott, International Women’s Year: The Greatest Consciousness-Raising Event in History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 115–127.

[10] Suely Rolnik, “The Spheres of Insurrection: Suggestions for Combating the Pimping of Life,” e-flux journal 86 (November 2017). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/86/163107/the-spheres-of-insurrection-suggestions-for-combating-the-pimping-of-life/

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] For further reading on the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, see Diana Taylor, Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War” (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997).

[14] Uhart passed away in 2018, just two years after the video was filmed.

[15] For an excerpt of Así lo hago yo, follow this link: https://vimeo.com/451908439

[16] “Everyone has the right to pleasure.”

[17] For more information on Nosotras Proponemos, visit http://nosotrasproponemos.org/

[18] Pañuelazo is a term that is difficult to translate into English. It derives from pañuelo [handkerchief], objects that, when green, are symbols of pro-abortion rights and are ubiquitous at Ni Una Menos demonstrations. In this sense, pañuelazo refers to these mass demonstrations. In terms of veganism, many feminists take an eco-feminist point of view, which asserts that the oppression of women and animals is intricately intertwined in Western patriarchal systems of power.