A View from the South: New (and Feminist) Narratives of Argentine Art

As a feminist, working-class, and mid-career scholar, I would have never expected to write the personal and professional narrative I am about to begin.[1] In 2019, I was offered a unique chance: the Artistic Director of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (link: https://www.bellasartes.gob.ar/) of Argentina, Mariana Marchesi, called me to curate a pioneering show in the institution’s history. Many factors – including the COVID-19 pandemic – delayed the opening of El canon accidental. Mujeres artistas en Argentina (1890-1950) [The Accidental Canon. Women Artists in Argentina (1890-1950)], which finally opened in March 2021 and remained on view until November 2021.

[El canon accidental. Mujeres artistas en Argentina (1890-1950), gallery entrance, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, March 23 – November 7, 2021.]

After years of being called out for not exhibiting the works of women artists of its collection (link: https://elpais.com/cultura/2018/03/08/actualidad/1520528459_321185.html), the museum has begun a process of reassessment of its own practices. One of the main initiatives was the organization of El canon accidental. Mujeres artistas en Argentina (1890-1950) (link: https://canonaccidental.bellasartes.gob.ar/): the first exhibition of its kind to be held at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. As part of the museum’s commitment to the project, Mariana Marchesi assembled a research team that has explored all-female shows in the history of the museum and has also created a database of all the women artists who are part of the museum’s holdings.

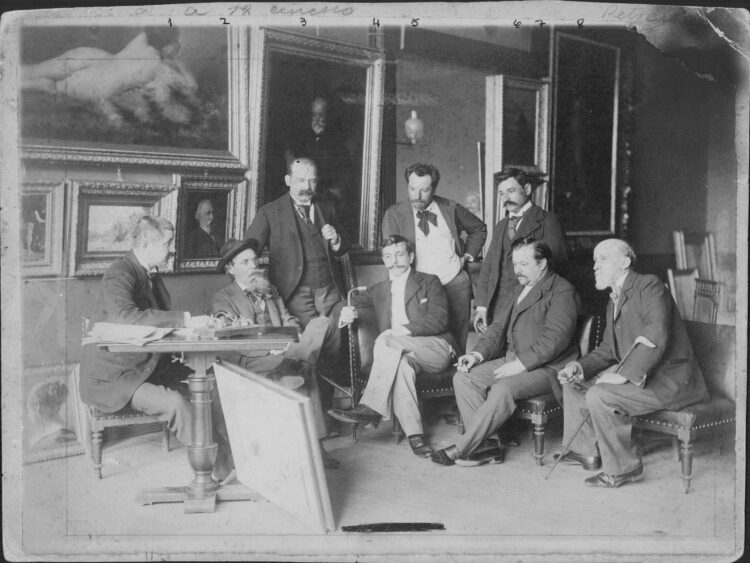

My research has always focused on Argentine women artists and gender in art. This knowledge – that I am passionate about – disrupts the patriarchal canon, perfectly embodied in both the history and the collection of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. The main figure in the conception of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes was its founder and first director, Eduardo Schiaffino, an artist and a pioneering figure in art history.

[Eduardo Schiaffino, first from the left, during a jury meeting for the art show at El Ateneo, 1893.]

In Argentina, several major individual exhibitions by women artists had been put on from the end of the 2000s onwards: in 2009, the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano organized an exhibition on the careers of Yente and Lidy Prati (link: https://www.malba.org.ar/catalogo-yente-prati/), participants in the development of abstract and concrete art, who finally received their due recognition after years of being overshadowed by their romantic partners, Juan del Prete and Tomás Maldonado.

In 2011, the same museum hosted the first research-based retrospective of Marta Minujín (link: https://www.malba.org.ar/catalogo-marta-minujin-obras-1959-1989/), a central figure the Argentine art history and undoubtedly the most widely known woman artist in the country. Finally, in 2015, the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano began a series of exhibitions dedicated to rediscovering the contributions of Latin American women artists “to the construction of female identity”,[2] i

in the words of the then Artistic Director, Agustín Pérez-Rubio.

The feminist debate questioning the masculinist canon appears to have begun to have concrete results in public museums as well. Shows such as A la conquista de la Luna, curated by Mariana Marchesi at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in 2018, presented “women artists” as a political category and as a site of cultural, not biological, difference. We are witnessing an era where women artists are increasingly visible, particularly those active from the 1950s. But women artists before the 1950s… that is a whole different subject. Except for Raquel Forner, an almost mythical figure around whom a legend has been created, the public has had little access to the works and careers of artists of the years before the 1950s.

[Raquel Forner at her solo show at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, 1962.]

The idea that women faced abysmal obstacles during the nineteenth and early twentieth century that prevented them from developing an artistic practice is strongly rooted in Argentine bibliography The discourse of obstacles, which minimizes the artistic activities of women, has affirmed that – before the 1950s –female production had established limits, in what Kirsten Swinth has called the stereotype of the flower painter.[3]

These narratives are difficult to defuse not only because of the patriarchal nature of the discipline of art history but because of the problems in finding sources and works that allow us to know the trajectories, works, and lives of women artists. Regarding the possibility of writing these artists into art historical narratives or attempting to recreate the discipline by considering these artists, the disappearance of both personal documentation and works by women artists makes the construction of artistic personae – following the models installed for male artists – a difficult task.

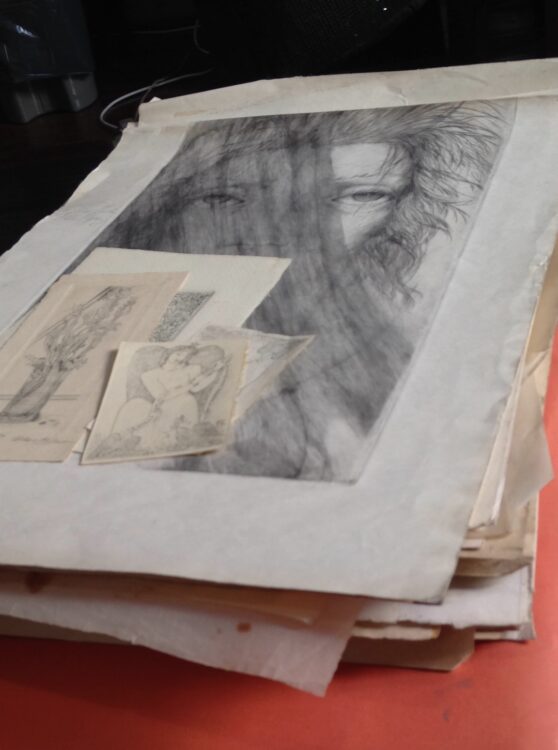

Excluded from dictionaries, monographs, and catalogues, artists and their works can only be restored to the general history of art through time-consuming research that assembles the most heterogeneous sources. The search for references in newspapers, magazines, and contemporary books is the main way to get to know the women artists up to the 1950s. The absence of archives that allow a deeper approach to the way of life and thought of these artists represents a massive obstacle. The descendants of the artists play a key role in the process of reconstruction and analysis of their careers, preserving archives that have not attracted institutions and that have only recently been opened for consultation.

[María Carmen Portela’s personal papers, currently at her granddaughter’s house.]

The physical disappearance of archival material and works created by women artists have posed major challenges for El canon accidental. However, we managed to gather more than one hundred works, alongside documents, of forty-four women artists active between 1890 and 1950.[4]

The show was organized in three different sections. The first one covered the period from 1890 to 1911; the second started in 1911 and ended in 1935; the last finished in 1950. They explored topics such as women artists’ involvement with diverse artistic genres, women artists’ visibility, women’s achievements in several media, and women’s approaches to the body in art.

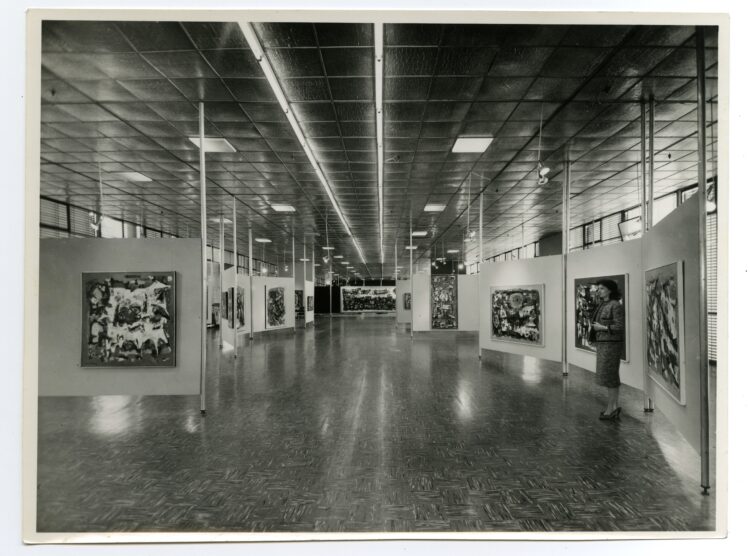

[El canon accidental. Mujeres artistas en Argentina (1890-1950), installation view, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, March 23 – November 7, 2021.]

Only two of the almost twenty works that were included in the first section of El canon accidental are part of the museum’s collection. The other works come from two main sources: the artists’ families and the Museo Histórico Nacional, which aimed to educate the public and to foster patriotic feelings through the exhibition of images that showed “our” founding fathers, key battles, and other relevant events. The value of the works in the historical museum did not rest so much on the artists’ skills but on the alleged veracity of the representation. Hence, the artists’ names were not the most important aspect for their inclusion in the museum’s collections. Women artists had everything to gain in this situation and played a role in the formation of the collection.

[Sofía Posadas, El sueño de San Martín, 1900, oil on canvas, 79 x 100 cm, Museo Histórico Nacional Buenos Aires.]

In 1911, the first edition of the Salón Nacional (National Salon) took place. Even if the presence of women did not grow steadily in the salon, it still proved to be an exciting venue to gain public recognition and enter the collection of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, among other collections. The museum has a rich selection of some of the key women artists from the 1910s to the 1940s. Even though they are still underrepresented, women artists of this period are easily found in the collection of the museum. Their works were acquired, for less money of course, but women were eager to be represented at the museum.

[Ana Weiss, El vestido rosa, circa 1915, oil on canvas, 140 x 100 cm, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires.]

This was quite obviously connected to these artists’ social class. Most of the artists active in Argentina during this period – and it could be argued that the situation has not changed that much – belonged to upper-middle-class or even to a solid upper-class of landowners. This undeniable fact causes – from my own lugar de fala – in Djamila Ribeiro’s words,[5]

some cognitive and even affective noise. The question of how universal the idea of “woman” is keeps returning. Black, indigenous, trans, decolonial, and working-class approaches to feminism have critiqued white feminism from their specific positions of disempowerment. As Rosana Paulino highlighted during our meeting, how could she – whose mother was a domestic worker – feel part of the feminist movement, whose participants were able to engage in it because someone else (in this case, poorly paid women in a position of lesser power) was in charge of cooking and cleaning, i.e. the so-called natural tasks of women? Yet, I feel that to some extent these women’s struggles have a lesson to teach us: privilege is a spectrum and even privileged women must face some degree of violence, especially in the male-defined art world.

The desire to re-write women into art histories is the driving force of researchers who are passionate about the achievements (and failures) of women of the past. The logic of academic production imposes times, deadlines, and an abundance of publications that simply do not work with the enormous efforts that must be made to reconstruct forgotten biographies and to study works stored in museum reserves, at best.

[Cecilia Marcovich, La mujer en marcha, pencil on canvas, 1947, private collection.]

It would be very difficult to assert that the artists – whose memory has survived and that have left traces of their existence in the historical record – are the most important, the most visible in their time, or the most representative (regardless of how we define these highly elusive concepts). Preservation is often random and introduces the shadow of a doubt in all inquiries about women artists of the past. At the same time, this widespread uncertainty helps us understand that feminist criticism of art history is a force capable of questioning the entire discipline – not a small problem in an otherwise serious and established discipline – as Linda Nochlin noted in 1971.[6]

I often wonder what is feminist about El canon accidental. I would say that embracing uncertainty when thinking about women artists, instead of trying to avoid it or covering it up, is a key for the many approaches to the multifaceted feminist project in art history.

By: dr. Georgina G. Gluzman

[1] This text was partially rewritten after the 22 November 2021 meeting of the group with Marina Gržinić and Rosana Paulino.

[2] Agustín Pérez Rubio and Victoria Giraudo, Annemarie Heinrich, Secret Intentions. Genesis of Woman’s Liberation in her Vintage Photographs, Buenos Aires, Fundación Eduardo F. Costantini, 2015, p. 20.

[3] Kirsten Swinth, Painting Professionals. Women Artists and the Development of Modern Art, 1870-1930, Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2001, p. 73.

[4] I use the plural “we”, for any curatorial project is by nature a collective endeavor.

[5] Djamila Ribeiro, O que é lugar de fala?, Belo Horizonte, Letramento, 2017. I am grateful to Dr. Talita Trizoli, among many other things, for pointing out some of the controversies surrounding Ribeiro, who has acted as a spokesperson for a Brazilian mobility-as-a-Service provider. As every form of critical acting, including art, Ribeiro’s practice can be (and has been) coopted by capitalism. In the case of many of the shows mentioned throughout this text, artwashing has played an outstanding role. Artwashing practices have been seeking to erase from the public consciousness the process of environmental destruction carried out since the 1990s in Argentina, among many other forms of capitalistic violence.

[6] Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, In Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays, New York, Harper & Row, 1988, pp. 145-178 [1971].