Anni Albers’ Theorisation of Textiles: Interwoven Narratives of the 20th Century Art

Author: Marina Vinnik

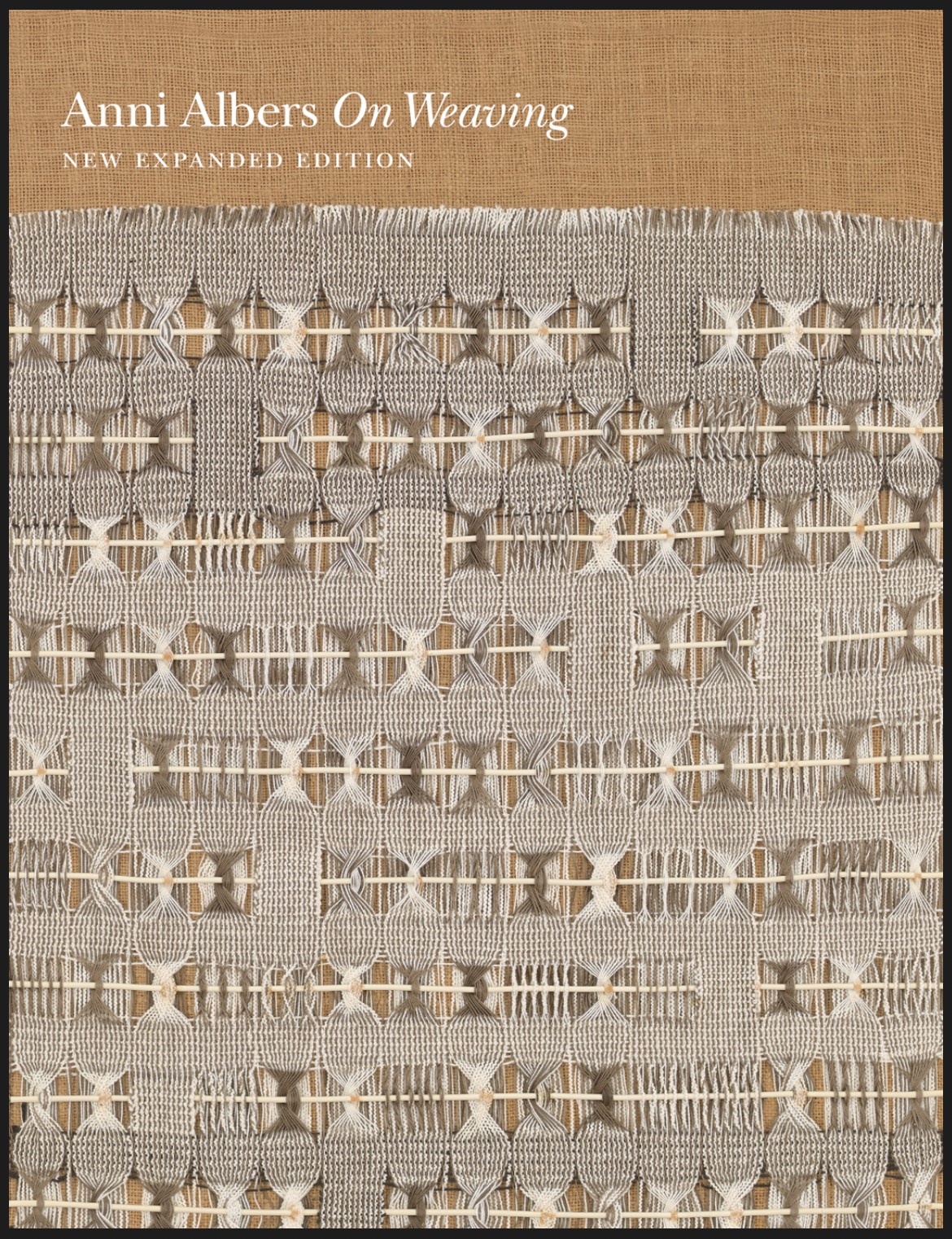

Anni Albers. On Weaving (2017 edition)

The life and work of Anni Albers (1899 – 1994), born Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann, embodies many key narratives of the 20th century and provides truly fascinating research material. Born to a Jewish family in Berlin Charlottenburg, she found a productive artistic path and survived the atrocities of the 20th century. Anni Albers can be viewed through multiple lenses: as a Jewish woman, as a woman artist, as a textile artist, and as a migrant artist. It seems that Anni Albers was able to find sources of inspiration and resistance at every turn of her complicated life.

Being a Jewish woman in the beginning of the 20th century in Germany was far from easy. Nevertheless, Albers moved from the large multi-cultural city of Berlin to the small city of Weimar to join the new experimental Bauhaus School in 1922. As an institution at the beginning of the 20th century in Germany, Bauhaus had a significant number of Jewish students, but at the same time experienced all the unfortunate pressure of the growing fascist movement during the interwar period.

Nowadays, if you want to take a tour through Bauhaus historical sites, this will take you first of all to Weimar, then to Dessau, and finally to Berlin. Notably, another place of interest that attracts audiences in Weimar is the former concentration camp of Buchenwald, whereas Dessau has Dessauer Wagonfabrik concentration camp, and Berlin is also full of the sites that commemorate the Holocaust.

Antisemitism and the subsequent Nazi-Germany government that started the Second World War were the key players in the fate of the Bauhaus School . Bauhaus designs look modern and in no way related to wars and suffering; in contrast, they represent a strong interest in modern and comfortable peaceful living (without forgettingthe exception of the Bauhaus font that was designed specifically for Buchenwald). Every person involved in the design production was in one way or another deeply affected by the historical context.

Today, one can trace the way in which Bauhaus School responded to the rising tensions in Germany by taking a tour through the key museum sites. The history starts at the small town of Weimar (currently around 60 000 people), with the Bauhaus Museum Weimar that played a vital role in the local modernist narrative. The history of Bauhaus starts even before the famous new school, with a Belgian architect and designer, Henry Clemens van de Velde, who opened a School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar (van de Velde was not allowed to continue his work due to his Belgian citizenship while Germany was preparing to the First World War),

Walter Gropius was his successor, and the Bauhaus School in Weimar was opened at the start of the Weimar Republic in 1919. Sadly, the Bauhaus School was only able to remain in the city of Weimar till 1925, due to the growing tensions between the Bauhäuslers and the locals and the lack of financial support. In 1925, a decision was made to move to Dessau, a city in the same area, closer to Berlin. And finally, in Dessau, the functioning of the school became impossible again in 1932. Bauhaus then moved to he capital Berlin and was completely dismantled in1933. Anni Albers, first by herself, later together with her husband and a former teacher Joseph Albers, moved with the school.

Anni Albers as an artist can also be considered as two threads connected in one woven textile. She was simultaneously a Jewish woman in antisemitic Germany and a textile artist, who even today is one of the key representatives of the German-based Bauhaus School . Perhaps, Albers‘ Jewish identity allowed her to sense the logic of the rapidly changing zeitgeist. In 1933, she and her husband left Germany and moved to the United States of America at the first opportunity. The timing of this move was crucial because a longer residence could have cost Anni her life. For instance, her colleague and peer, a textile artist of a Jewish origin Otti Berger (1898-1944), went back to Yugoslavia and died in Auschwitz in 1944. ,

Staying in Germany during the war, though, made not only Jewish artists vulnerable, Albers’ colleague, the textile artist Alma Siedhoff-Buscher (1899-1944), died in 1944 during an air raid. Anni Albers survived the Second World War and followed the news from the overseas. In 1965, Berlin Jewish Museum offered her the opportunity to make a work commemorating the Holocaust, and she created the textile Six Prayers (1965-66). Today, this work is in the permanent collection of the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

Anni Albers. Six Prayers (1965-66), cotton, linen, bast, and silver thread. Jewish Museum Berlin.

Surviving the most brutal massacre of the 20th century, Anni Albers ended up in the United States of America, as did many of her colleagues who had left Europe right before the outbreak of the Second World War. Her sphere of artistic work was textile, textile design, and weaving. The way young women artists were pushed towards textile practice in the Bauhaus School would now be interpreted as purely sexist. At first, the male dominated and therefore prestigious sphere was painting, and later the focus shifted to architecture. Meanwhile, textile and ceramics were perceived more as craft and mindless occupation for ones hands than serious art, as in the infamous quote by one of the Bauhaus’ masters, Oskar Schlemmer: “Where there is wool, there is a woman who weaves, if only to pass time.”

The impulse of the Bauhaus masters, such as Walter Gropius, Oskar Schlemmer and Georg Muche, was to separate men and women and let women work in their own unprestigious field. This process of feminization of textile workshops is discussed by Sigrid Wortmann Weltge[1] and Anja Baumhoff[2] in their insightful publications on gender and weaving in the Bauhaus School. Gender division upset many of the artists, the most prominent example being Gertrud Arndt (born Gertrud Hantschk (1903-2000)), who wanted to study architecture initially, but ended up working with textiles and photography. Arnd’s fate was turned into an artistic project of another woman artist, Gabi Schillig, who created models of buildings out of her textile designs.[3] In the end though, this ghettoization supported the formation of female connections and an establishment of quasi-female-only collectives. The combination of so many talented women in one workshop, Gunta Stölzl, Anni Albers, Otti Berger, Benita Otte, Gertrud Arndt, Lilly Reich, Grete Reichardt, and the spirit of innovation and industry raised Bauhaus textiles to an incredibly high level, and they still remain the business card of the school. Interestingly, textiles quickly became the most profitable venture of the Bauhaus and brought the most significant income. It is still visible in the gift shops of the local museums, and the most expensive textile made by Anni Albers is Eclat (1974), whose price was 1.5 million dollars in 2018.

In recent years, multiple researchers have written about Bauhaus weaving theory, most notablyT’ai Smith in her book Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design (2014). In the recent Routledge Companion to Women in Architecture[4], Harriet Harris published the text Blocks versus Knots: Bauhaus Women Weavers’ contribution to Architecture’s Canon, where she emphasises the significant contribution of textile artists to the architectural projects:

“That the Bauhaus Dessau building façade by architect Walter Gropius resembles the warp and the weft of a loom is a subjective suggestion. And yet there are many similarities between how surfaces and structures are conceived in architecture and textiles.”

All this prolific theoretical work would not have been possible without Anni Albers’ deep involvement in architectural and textile theories and without the texts that Albers, Berger, and Stölzl published.

Anni Albers was married to an architect and painter Joseph Albers; therefore, there is a likelihood that she may have noticed how much painting and architecture were supplemented by theoretical work and how much they rely not only on manual (the famous learning through doing), but on textual process. This is something, that seems obligatory today, when every art student is expected not only to produce art, but also be able to write theoretical texts.

Even before her emigration from Germany, Albers had already published the article: Bauhausweberie (1924). While working and teaching in the Black Mountain College, she was able to write her most influential books On Designing (1959), where she has a part “The Pliable Plane: Textiles and Architecture” and On Weaving (1965), a book that was based on her curriculum and teaching. A serious and theoretical approach to textiles and a palpable attempt to elevate them from mundane craftwork to structured experimental artistic practice is very much in the spirit of early feminist art history, as found in the United States of America. In 1989, Rozsika Parker published her The subversive stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine,[5] where she likewise discussed gender and textile.

Anni Albert’s quote from the book On Weaving, that is used as an epigraph by T’ai Smith:

“Just as it is possible to go from any place to any other, so also, starting from a defined and specialized field, can one arrive at a realization of ever-extending relationships. Thus, tangential subjects come into view. The thoughts, however, can, I believe, be traced back to the event of a thread”

This shows the path for every artist to the multi-faceted interweaving and combining of such things as art, theory, craft, design, materials, gender, history, and life itself.

[1] Weltge-Wortmann, Sigrid. Bauhaus Textiles: Women Artists and the Weaving Workshop.1993

[2] Baumhoff, Anja. The Gendered World of the Bauhaus: the Politics of Power at the Weimar Republic’s Premier Art Anstitute, 1919-1932. 2001

[3] https://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/de/programme/bauhaus-residenz/gabi-schillig.html

[4] Sokolina, Anna, ed. The Routledge Companion to Women in Architecture. Routledge, 2021

[5] Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. 1989