Freedom versus freedom: from late sovietness to post-ness and back again*

Self-construed heterodox consciousness writes the years preceding the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics into the story of freedom that was reached through the pain and agony of history – individual powerlessness and suffering against the violence of the system; this historical juncture gave rise to the practice of discourse whose telos was the fulfilment of freedom and liberty in a formerly unfree society.[i] From here emerges the view of the nadir of Soviet Socialism (mid-1980s to 1991) as a tear in the fabric of modernity, and of equal world-historical significance as the proletarian revolution of 1917.[ii] The period of late Soviet modernity was ossified in the annals of heterodoxy as the moment pregnant with radical change; in that sense, it bears the birthmark of the historical rift between the revolution and counterrevolution, the old and the new, late sovietness and post-ness.

At the definitional level, heterodox consciousness is predicated upon the logic of dissidence, taking its historical roots in the circles of cultural resistance formed during State Socialism; dissident forms of thought and action are prevailing today, albeit in a changed form, in such milieux as, for example, the self-identified left in academia and journalism, socially engaged arts and crafts, youth and popular culture. At the heart of the logic of dissidence is an assumption of the possibility and potential of social organizing beyond ideology or direct political engagement; another key aspect of the logic of dissidence is its understanding of historical change, moved forward by the self-activity of actors within the vast and avowedly autonomous field of culture that exists parallel to state power but does not converge with it.

Looking for the meaning of late Soviet modernity in the tumultuous 2020s, I would like to examine late sovietness and post-ness comparatively. My reflection stems from a general tendency – the enactment of the politics and policies of democracy in Russia today[iii] vis-à-vis the construct of the 1990s as order in anarchy[iv] – but is concerned with the specific way in which heterodox consciousness fulfils the promise of freedom that it has historically bestowed upon itself.

The myth of Timur Novikov

In the eyes of heterodox consciousness, history takes the form of myth; to borrow my working definition of myth from Roland Barthes, “Myth is a language” – written, spoken and pictorial – we use in “our bourgeois world.”[v] An enactment of this kind of language can be traced in the biography of Timur Petrovich Novikov (1958-2002) – or simply Timur – an art and craft practitioner working since late Soviet modernity in Leningrad, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

- Timur Novikov, Aurora, 1990, acrylic on canvas, 70х40 cm. https://timurnovikov.com/en/works/НТ171

As his contemporaries acknowledge, Novikov has been a keen “mythologist” and a playful “mystifier.”[vi] Indeed, to make sense of Timur Novikov as a myth requires an appreciation of the “mythology of the mythologist,”[vii] which embraces a whole variety of nascent phenomena booming in the late Soviet era: rave and club culture,[viii] the music and film industries, art curating and design.[ix] A concise mapping of this bourgeoning scene would be far too ambitious a goal: as the myth goes, Timur and his peers constituted a full-fledged movement[x] for a “cultural revolution” in the late Soviet era.[xi] The figure of Timur Novikov brings to bear the standpoint of heterodoxy coming to its consciousness of history and yet articulating itself as a myth.

According to this myth, Timur’s oeuvre breaks down into three major episodes: the Chronicle[xii] group of the late 1970s, practising painting, primitive art and expressionism;[xiii] the New Artists[xiv] movement of the early 1980s, embodying the anarchist spirit of freedom[xv] and autonomy of artistic production; and Neo-Academism, pursuing the imagery of Enlightenment and Europeanness from the mid-1990s onwards as a contentious expression, or perhaps even mockery of neo-conservativism and neo-nationalism in neo-liberal times.[xvi]

I would like to focus on the second episode of the myth, when craft labour – “tatters,”[xvii] in Timur’s ample expression – was elevated to the status of technology to rebuild a movement of youth culture from the remnants of the old underground culture.[xviii] The case of the New Artists speaks directly to the question of heterodoxy coming to its consciousness during late Soviet modernity: the movement authorised itself as the denotatum of anarchism in culture, by embodying the visionary romantic subject, whose main occupation was playful idleness, and who existed blissfully[xix] in pursuing itself as an organic expression of “life as a whole.”[xx]

The alluring complexity of the politics of anti-politics involved in the second episode of the myth of Timur Novikov allows us, on a theoretical level, to complicate the history of craft labour as defined by recognition of the subject’s gender/sex,[xxi] as it also allows us to question the strategy of art historical analyses that situate the category of gender/sex in the symbolic realm of subject construction but in fact reinforce the agenda of right-wing feminism, as if the theme of gender/sex liberation falls beyond the domain of ideological beliefs.[xxii] Contrary to the latter position, for heterodox self-consciousness, history takes up the form of the myth so as to manifest itself as an ideological value and also a value to be consumed.[xxiii]

- Timur Novikov, Don Quixote Meeting the Red Sun, 1988, acrylic on textile, 144х134 cm. https://timurnovikov.com/en/works/ТН102

- Timur Novikov, The New, 1988, acrylic on textile, 132х92 cm. https://timurnovikov.com/en/works/ТН113

- Timur Novikov, The Suit, 1988, acrylic on fabric. https://timurnovikov.com/en/works/TN76A

- Timur Novikov, The Sun, 1989, acrylic on textile, 137х138 cm. https://timurnovikov.com/works/ТН162

- Timur Novikov, Oasis, 1989, acrylic on textile, 111×94 cm. https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/russian-pictures-2/oasis

- Timur Novikov, Sunrise, 1989, acrylic on textile, 109×107 cm. http://www.artnet.com/artists/timur-novikov/sunrise-HpO9jg43T3c56cmnzxfrsg2

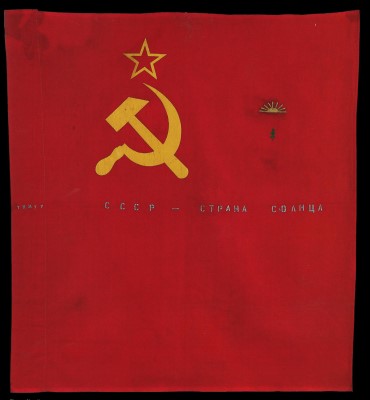

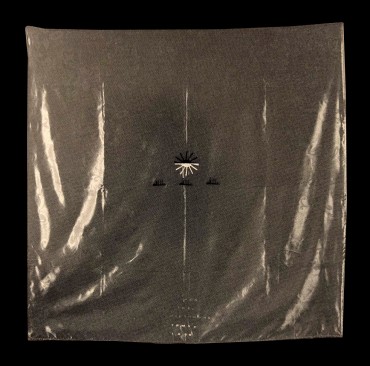

- Timur Novikov, The USSR – The Land of the Sun, 1989, acrylic on textile, 80х73 cm. https://timurnovikov.com/en/works/НТ145

- Timur Novikov, The Cruiser Aurora and the City of the Three Revolutions, 1989, acrylic on textile, 100х100 cm. https://timurnovikov.com/en/works/НТ96

- Timur Novikov, The Cropper, 1991, acrylic on textile, 234×144 cm. https://vladey.net/ru/lot/4318

The fetish character of heterodox consciousness

An essential part of the second episode of the myth is the iconography of the sun, prominent in Timur’s textiles since the time of the New Artists.[xxiv] The sun icon is the avatar of heterodox self-consciousness thrown into the universe of myth and changing its appearance as time goes by: the transformation of the value of craft labour – in addition to the increasing fetishization of heterodox consciousness – takes place after Timur’s death, when his textiles had become a commodity for the super-rich[xxv] and a commodity reproducible on a mass scale. The sun sign connects and fixates the two aspects of craft labour – oneness and multiplicity – on the arrow of time. And while it would be wrong to divorce these two aspects, I think it is the latter, multiple fragments of Timur’s textiles rolling off the assembly line after his death, that mark the shift in heterodox consciousness in the period of post-ness. The figure of Timur Novikov reshapes itself into a full-fledged artefact of heterodoxy in the period of post-ness: not only from the standpoint of the “Last Soviet Generation”[xxvi] but also Generation Z.[xxvii]

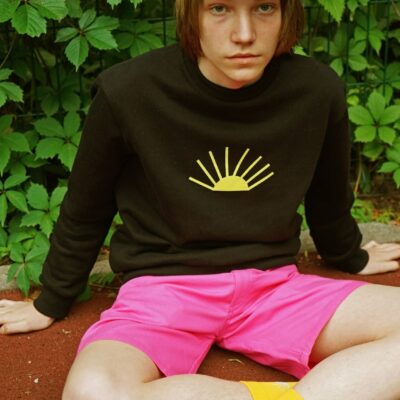

Crawling through the annals of heterodoxy is craft labour post-mortem: in 2015, a fashion brand under the name “Gosha Rubchinskiy” began to cite Timur’s iconography of the sun. The fashion media vividly portrayed Timur Novikov “re-enter[ing] the cultural consciousness via the sweatshirts and t-shirts of Gosha Rubchinskiy.”[xxviii] While the icon of the sun, as it were, travelled from tatters to t-shirts, the heterodoxy of the late 1980s and early 1990s became a historical point of reference in the market of youth culture on the verge of high fashion:[xxix] all to degenerate heterodox self-consciousness to the status of a thing, sold at the Dover Street Market in London, New York, and Japan, and in the Trading Museum in Paris.[xxx] According to Rubchinskiy’s promotional materials, “Timur’s emblematic and elusive designs are eerily poised for contemporary style codes: those graphics are simple but disarming, with a subversion that speaks louder than slogans.”[xxxi] The sun icon thus “speaks” of the ideological value of anarchism in culture the New Artists stood for, yet when refurbished into a code of style, this value reemerges as the means for fashioning the Gen Z self.

- Gosha Rubchinskiy and Timur Novikov, 2015 Capsule Collection. https://www.pinterest.co.kr/pin/21744010678708732/

- Gosha Rubchinskiy and Timur Novikov, 2015 Capsule Collection, photography and styling by Gosha Rubchinskiy. https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/gallery/20180/7/gosha-rubchinskiy-x-timur-novikov

- Gosha Rubchinskiy and Timur Novikov, 2015 Capsule Collection, photography and styling by Gosha Rubchinskiy. https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/gallery/20180/9/gosha-rubchinskiy-x-timur-novikov

- Gosha Rubchinskiy and Timur Novikov, 2015 Capsule Collection, photography and styling by Gosha Rubchinskiy. https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/gallery/20180/5/gosha-rubchinskiy-x-timur-novikov

- Gosha Rubchinskiy and Timur Novikov, 2015 Capsule Collection, photography and styling by Gosha Rubchinskiy. https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/gallery/20180/8/gosha-rubchinskiy-x-timur-novikov

Concurrently, this “spectacle of signification”[xxxii] is not only about converting historical heterodoxy into a code of style; late sovietness has been mobilised, above all, as a marker for authenticity, truth, and freedom – lost and buried in the late 1980s and early 1990s; the fashion designer Gosha Rubchinskyi is the one, who, according to his account,[xxxiii] reaches back to the past, rediscovers the spirit of freedom[xxxiv] that the “Last Soviet Generation” was lucky, however briefly, to live through. Such self-stylized reconstruction of the late Soviet imagination of freedom in 2015 equates freedom with a consumer and/or lifestyle choice to make,[xxxv] and in doing so, it spells out the present as having been emptied out, reaffirming freedom as exiting in the past only – as a memory.[xxxvi] The fact that Rubchinskiy’s brand had petered out by 2018[xxxvii] is far from spelling doom for the manufacture and repression[xxxviii] of the desire for liberation.

Freedom versus freedom

The case of Timur Novikov and Gosha Rubchinskyi shows that inquiring into heterodox self-consciousness and its sense of historicity means encountering the recurring character of late sovietness. As historical heterodox consciousness undergoes change, it recoils, simultaneously as a cultural commodity and a designatum of freedom. The past endures in its becoming. But saying so is different from affirming, for example, the USSR’s grandeur to loom in Eurasia,[xxxix] or the politics of Putinism as the organic result of the late 1980s and early 1990s,[xl] or an inherent “continuity between the nonofficial culture of socialism and the post-Soviet youth culture” in their evolution from the “Temporary Autonomous Zones” to the enduring circuits of consumer wants and self-marketing.[xli] What underlies these figures of thought is reminiscent of historicism’s rationale of causality,[xlii] whose actual interest is to obfuscate the present as a historical problem,[xliii] thus shying away from capital’s cloven-hoofed dynamics of recurrence.

Treating the present as a historical problem brings to the forefront the rich complexity of heterodox self-consciousness and its self-location in time; profoundly so if the latter turns into a principle for eluding the task of the present in a wishful trope of the “spectacular collapse of the late socialist symbolic order in the early 1990s.”[xliv] It did not collapse;[xlv] it keeps on living, breathing, decaying. And it urges us to question: how not to digress from realising the task that the past has bestowed upon us – the task of fulfilling freedom and liberty in a formerly free society?

- Timur Novikov, 1990, The Object, acrylic on glass, 30х30 cm, photo by Peggy Jarrell Kaplan. https://timurnovikov.com/works/НТ165

By: Natalya Antonova

* This essay was presented during the research seminar Narrating Art and Feminisms in Eastern Europe and Latin America in March 2022; I would like to thank Agata Jakubowska and Madeline Murphy Turner for their comments on an earlier draft of the text. I am deeply grateful to Professor Erzsébet Barát and Professor Anca Oroveanu: had it not been for their help and support, this essay would not have been written. I owe thanks to the Melbourne Chapter of the Platypus Affiliated Society for organizing discussions that led to the writing of this essay; my special thanks go to Desmund, Duncan, Freya, Harry, Jonny, Leon, Liam, Maryann, Michael, Peter, Roman, Ryan, Samuel, and Shane.

Responsibility for misinterpretations and errors related to the text’s content falls upon the author.

[i] See, for example, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, ‘Zhyt Ne Po Lzhy [Live Not by Lies]’, 1974, http://www.solzhenitsyn.ru/proizvedeniya/publizistika/stati_i_rechi/v_sovetskom_soyuze/jzit_ne_po_ljzi.pdf

[ii] See Adele Marie Barker, ‘Rereading Russia’, in Consuming Russia: Popular Culture, Sex, and Society since Gorbachev, ed. Adele Marie Barker (Durham; London: Duke University Press, 1999), 4.

See also Václav Havel, ‘The Power of the Powerless’, 1978, https://hac.bard.edu/amor-mundi/the-power-of-the-powerless-vaclav-havel-2011-12-23.

See also Istvan Dobozi, ‘The ’90s in Russia: A Decade of Progress and a Prelude to Putin?’ (Wall Street Journal, 15 June 2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/russia-1990s-soviet-yeltsin-putin-oligarch-shock-therapy-11655238849

[iii] See Unauthored, ‘Putin Prizval k Priamoi Demokratii v Rossii [Putin Called for a Direct Democracy in Russia]’, 20 July 2022, https://news.ru/vlast/putin-prizval-k-pryamoj-demokratii-v-rf/.

[iv] See Jo Adetunji, ‘The Wild Decade: How the 1990s Laid the Foundations for Vladimir Putin’s Russia’ (The Conversation, 2 July 2020), https://theconversation.com/the-wild-decade-how-the-1990s-laid-the-foundations-for-vladimir-putins-russia-141098.

[v] Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: The Noonday Press, 1991/1957), 10.

[vi] See Andrei Khlobystin, ‘Kak Timur Novikov Sozdal “Novuiu Akademiui”? [How Did Timur Establish the “New Adademy”?]’ (Sobaka.ru, 2018), https://www.sobaka.ru/entertainment/books/79098.

[vii] Barthes, Mythologies, 11.

[viii] See Timur Novikov, ‘Kak Ia Pridumal Reiv [How I Invented Rave]’, 1996, https://timurnovikov.ru/library/knigi-i-stati-timura-petrovicha-novikova/kak-ya-pridumal-reyv.

[ix] See Andrei Khlobystin, ‘Kak Timur Novikov Sozdal “Novuiu Akademiui”? [How Did Timur Establish the “New Adademy”?]’, 2018, https://www.sobaka.ru/entertainment/books/79098.

[x] Polina Kozlova, ‘Kak Kultovyi Khudozhnik Timur Novikov Okazalsia Na Svitshotakh Goshy Rubchinskogo [How the Iconic Artist Timur Novikov Ended up on Gosha Rubchinskiy’s Sweatshirts]’ (Buro 24/7, 14 December 2016), https://www.buro247.ru/culture/expert/timur-novikov-zakonodatel-sovremennoy-mody.html.

[xi] Unauthored, ‘The New Academy. Saint Petersburg’ (Forum.ARTinvestment.RU, 4 November 2011), https://forum.artinvestment.ru/blog.php?b=136878&goto=next

[xii] Rus. letopis.

[xiii] See I. Potapov, ‘Novye Khudozhniki [The New Artists]’, 1996/1986, https://timurnovikov.ru/library/stati-timura-novikova-izdannye-pod-psevdonimom-igo/novye-khudozhniki.

[xiv] Rus. novye khudozhniki.

[xv] Ivor A. Stodolsky, ‘A “non-Aligned” Intelligentsia: Timur Novikov’s Neo-Avantgarde and the Afterlife of Leningrad Non-Conformism’, Studies in East European Thought 63, no. 2 (May 2011): 136.

See also Ekaterina Andreeva, ‘Timur Novikov and the New Artists’, in The Oxford Handbook of Soviet Underground Culture (Online Edition), ed. Mark Lipovetsky et al., trans. Thomas Campbell, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197508213.013.29.

[xvi] Cf. Maria Engström, ‘Metamodernizm i Postsovetskii Konservativnyi Avangard: Novaia Akademia Timura Novikova [Metamodernism and Post-Soviet Conservative Avant-Garde: Timur Novikov’s New Academy]’, Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, no. 151 (2018), https://www.nlobooks.ru/magazines/novoe_literaturnoe_obozrenie/151/article/19762/.

See also Timur Novikov, ‘Avtobiografiia Timura Novikova [The Autobiography of Timur Novikov]’ (Look at me, 2008/1998), http://www.lookatme.ru/flow/posts/art-radar/53405-avtobiografiya-timura-novikova.

[xvii] Rus. triapochki.

[xviii] Andrey Khlobystin, Shyzorevoliutsyia. Ocherki Peterburgskoi Kultury Vtoroi Poloviny XX Veka [Schizorevolution. A Study on St Petersburg’s Culture in the Second Half of the 20th Century] (St Petersburg: Borey Art, 2017), 107–8.

See also Stodolsky, ‘A “non-Aligned” Intelligentsia: Timur Novikov’s Neo-Avantgarde and the Afterlife of Leningrad Non-Conformism’, 138.

[xix] Khlobystin, Shyzorevoliutsyia. Ocherki Peterburgskoi Kultury Vtoroi Poloviny XX Veka [Schizorevolution. A Study on St Petersburg’s Culture in the Second Half of the 20th Century], 42, 127–28.

[xx] Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread and Other Writings, ed. Marshall Shatz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005/1906), 154.

[xxi] Cf. Heather Pristash, Inez Schaechterle, and Sue Carter Wood, ‘The Needle as the Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power’, in Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles, 1750-1950, ed. Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009), 13–29.

[xxii] Cf. Suzana Milevska, ‘Talk: An-Archiving of the Archive: South-East Archives from a Feminist Perspective. 25 April 2022. Research Seminar: Narrating Art and Feminisms: Eastern Europe and Latin America. Institute of Art History, Faculty of Culture and Arts, Warsaw University.’

[xxiii] “Myth is a value, truth is no guarantee for it.” Barthes, Mythologies, 122.

[xxiv] See, for example, Vladey auction lots: https://vladey.net/ru/lot/7694; https://vladey.net/ru/lot/4318.

[xxv] See Klub Druzei Maiakovskogo [Maiakovskii’s Friends Club], ‘Iskusstvo i Kommertsyia: Otktrytoe Pismo o Nasledii Timura Novikova i Georgiia Gurianova [Art and Commerce: An Open Letter about the Legacy of Timur Novikov and Georgii Gurianov]’ (Colta, 10 August 2017), https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/15643-iskusstvo-i-kommertsiya.

[xxvi] “The Last Soviet Generation,” according to Yurchak, are those who were born between the mid-1950s and the early 1970s: see Alexei Yurchak, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005), 31.

[xxvii] According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, Generation Z (Gen Z) are the people born between the late 1990s and early 2010s.

[xxviii] See Claire Marie Healy, ‘The Radical Artist Who Shaped Russian Youth Culture’ (Dazed Magazine, 30 July 2015), https://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/25719/1/the-radical-artist-who-shaped-russian-youth-culture.

[xxix] See Kozlova, ‘Kak Kultovyi Khudozhnik Timur Novikov Okazalsia Na Svitshotakh Goshy Rubchinskogo [How the Iconic Artist Timur Novikov Ended up on Gosha Rubchinskiy’s Sweatshirts]’.

[xxx] See Ted Stansfield and Gosha Rubchinskiy, ‘Gosha Rubchinskiy Honours Russian Cult Artist’ (Dazed Magazine, 22 July 2015), https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/25592/1/gosha-rubchinskiy-honours-pioneer-of-russian-punk.

[xxxi] Healy, ‘The Radical Artist Who Shaped Russian Youth Culture’.

[xxxii] Roland Barthes, ‘Economy of the System’, in The Fashion System, trans. Matthew Ward and Richard Howard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990/1967), 288.

[xxxiii] Olivia Singer, ‘Ping Pong and Neo-Academism with Gosha Rubchinskiy’ (AnOther, 23 July 2015), https://www.anothermag.com/fashion-beauty/7624/ping-pong-and-neo-academism-with-gosha-rubchinskiy.

[xxxiv] Felix Petty, ‘The Forgotten 90s Rave Scene of St Petersburg That Inspired Gosha Rubchinskiy’ (i-D, 21 June 2017), https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/j5peb3/the-forgotten-90s-rave-scene-of-st-petersburg-that-inspired-gosha-rubchinskiy.

[xxxv] See Anastasiia Fedorova, ‘How Russian Youth Is Raving into a Bold New Future’ (Dazed Magazine, 19 June 2017), https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/36362/1/russian-youth-raving-in-moscow-arma-17.

[xxxvi] See Anastasiia Fedorova, ‘90s Reloaded: Freedom and Excess in a Wild Russian Decade’ (The Calvert Journal, Undated), https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/3929/intro-freedom-excess-Russian-90s-special-project.

[xxxvii] See Laura Morone, ‘What Happened to the Tsar of Streetwear Gosha Rubchinskiy?’ (Wait! Fashion, 16 June 2021), https://www.waitfashion.com/en/what-happened-to-the-tsar-of-streetwear-gosha-rubchinskiy/.

[xxxviii] “The culture industry does not sublimate; it represses.” Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, trans. John Cumming (London; New York: Verso, 1992/1947), 140.

[xxxix] See Gideon Rachman, ‘Understanding Vladimir Putin, the Man Who Fooled the World’ (The Guardian, 9 April 2022), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/09/understanding-vladimir-putin-the-man-who-fooled-the-world.

[xl] See Mark Lawrence Schrad, ‘To Understand Putin, We Need to Look at 1990s Russian Democratization’ (The Washington Post, 12 April 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/04/12/understand-putin-we-need-look-1990s-russian-democratization/.

See also Robert D. Kaplan, ‘Communism Still Haunts Russia’ (The Wall Street Journal, 8 June 2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/communism-still-haunts-russia-putin-stalin-czar-nicholas-culture-politics-war-officers-11654698674?mod=article_inline.

[xli] Yurchak, ‘Gagarin and the Rave Kids: Transforming Power, Identity, and Aesthetics in Post-Soviet Nightlife’, 79, 102-3.

[xlii] Walter Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’, in Selected Writings: Volume 4 (1938-1940), ed. Michael W. Jennings (USA: Harvard University Press, 2006/1940), 397.

[xliii] György Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1971/1923), 157.

[xliv] Yurchak, ‘Gagarin and the Rave Kids: Transforming Power, Identity, and Aesthetics in Post-Soviet Nightlife’, 79.

[xlv] Dmitrii Okrest, Stanislav Kuvaldin, and Evgenii Buzev, Ona Razvalilas. Povsednevnaia Istoriia SSSR i Rossii v 1986-1999 [It Dissolved. The History of Everyday Life in the USSR and Russia in 1986-1999] (Moscow: Bombora, 2022/2017).

yatogel I need to to thank you for this great read!! I definitely

enjoyed every bit of it. I’ve got you bookmarked to check

out new stuff you post