Interview with Gabriela Golder on her work at the Sharjah Biennial

By Andrea Giunta

Andrea Giunta: You’re participating in the Sharjah Biennial with several works. A very moving biennial, very touching, since the project started before the pandemic, curated by Okwui Enwezor, but, in the meantime, he passed away. He was an extraordinary curator, who transformed the way we view African art with radical exhibitions like The Short Century. The biennial, in a sense, honors his legacy (https://sharjahart.org/biennial-15/). On the other hand, the pandemic swept through the world.

Among the events that marked new scenarios in Latin America was the outbreak of October 2019 in Chile, which is linked to one of the works you are presenting at the biennial, Arrancar los ojos (Tear out the eyes), which featured a dazzling and emotional installation. Tell us first about this work.

Gabriela Golder: At the Biennial, I presented 3 works that are part of the Arrancar los ojos / Tear out the eyes project – in addition to the video installations Conversation Piece (from 2012) and Cartas (from 2018). It is a project that proposes a constellation of works around eye mutilation as a repressive method in popular demonstrations. It deals with the gaze and its political dimension. It was inspired by the shock of the tragic events that took place in Chile in October 2019: a social and political crisis that left more than 500 people with eye injuriess due to pellets fired by the police during the demonstrations. The victims lost one or both eyes.

What I read about this, the images I saw, haunted me. Several of my projects are born from this obsession – from an urge to understand something that is impossible for me to imagine. To think about the act of damaging and destroying someone’s eyes.

From this, from seeing all the images, from reading everything possible, I started to investigate. I started the research from the shock I felt.

The police aimed directly at the head. This does not happen only in Chile. It has also happened in Colombia, in Palestine, in France, in Hong Kong, in Brazil, in Lebanon, and in Egypt. Where else? Since when?

Tear out the eyes, part of these events, considers what immediately precedes the moment of mutilation, about the act and what remains after the tragedy. It examines the causes, the absence of sight, invisibility, and blindness. It also discusses possible ways to prevent a loss of memory: to collect what remains – the traces and images of those sights on the verge of disappearance.

Then, I had to think about how to go about this project. What institution could be interested in such a project? At first, I thought, none.

Then, in mid-2021, came the international call for FRAGMENTOS (Fragments): an exhibition space dedicated to memory in Colombia (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7rAb2O0JV8). I was receiving more and more news about the practice of mutilation in Colombia by the ESMAD (Mobile Anti-Riot Squad), which continued to be practiced until the middle of last year.

I thought that this demand could be a possibility, although I believed that, for the institution, it also implied taking a risk, supporting a project that was based on events that were happening there, in Colombia, at that time, carried out by state agencies, with the complicity of the government (we should bear in mind that the Fragments space is dependent on the Ministry of Culture). But the institution decided to take the risk and supported my project.

From that moment on, the project focused mainly on Colombia – not just Columbia – but Colombia was the starting point.

At that time, the project proposal was for two large video installations, plus a single-channel video.

I traveled to Colombia; I spent 5 days locked in a studio interviewing 10 victims of ocular damage. The interviews were to be the starting point.

The works are constructed from texts collected from various sources: slogans chanted in popular demonstrations in different regions of the world, testimonies of the victims of mutilation, military and scientific texts, chronologies, fragments of mythical texts related to the action of removing the eyes. These texts in different languages are spoken and sung in various musical styles. The staging incorporates large screens with video images of camera recordings taken from popular demonstrations. The expressions of those in the crowd are questioning. The slowed down gestures are abruptly cut off by texts that appear as newspaper headlines, subtitles, and calls to action.

A crowd crosses a large empty space. There are masks; there are animals; there are women, men, and children – hundreds of united and undifferentiated bodies. Laser pointers cross the air; these are actions of resistance. The images of control cameras of the repressive forces appear on the screen. The crowd is agitated, effervescent. It is the return of Goya’s Road to Hell. Some people detach themselves, look at each other, recognize each other. The mutilated crowd quietens down. Everything is extinguished. But the eyes insist; they recover the spaces; the bodies and the eyes return; they are restored. Is it possible to restore sight? Is it possible for the eyes to return to their sockets? Is it possible for them to rebel and do justice?

This work threads through historical and mythical time in search of the memory of the gouged-out eyes. It is a staging that, anchored in our present, navigates anachronistically among the stories of gouged out eyes. It interrogates them, invokes them, incites them to speak.

I filmed the victims in Colombia; I traveled to Neuquén to find some craters (I wanted to think of these craters as a resting place for the gouged-out eyes), I filmed the undifferentiated bodies in Buenos Aires, the staging of bodies in resistance; I filmed a scene on mythology, the mutilation of eyes in Greek mythology, and other scenes.

Furthermore, the performative gesture of finding the infinite ways of saying “tear out the eyes”: Tear out the eyes – Gouge out the eyes – Remove the eyes – Pluck out the eyes – Remove the eyes – Delete the eyes – Suppress the eyes – Extract the eyes – Exhume the eyes – Deplete the eyes – Empty the eyes – Withdraw the eyes – Steal the eyes – Steal from the eyes – Catch the eyes – Discard the eyes – Dispose of the eyes – Grift the eyes – Swallow the eyes – Lock the eyes – Jam the eyes – Grab the eyes – Grasp the eyes – Apprehend the eyes – Invade the eyes – Loot the eyes – Plunder the eyes – Pillage the eyes – Capture the eyes – Assault the eyes – Raid the eyes – Rob the eyes – Strip the eyes – Deprive the eyes – Embezzle the eyes – Dispossess the eyes – Undress the eyes – Separate the eyes – Detach the eyes – Kill the eyes – Murder the eyes – Shoot the eyes – Abolish the eyes – Prohibit the eyes – Ban the eyes – Forbid the eyes – Deprive the eyes – Deny the eyes – Stop the eyes – Refuse the eyes – Reject the eyes – Sentence the eyes – Condemn the eyes – Repudiate the eyes – Disown the eyes – Set aside the eyes – Dirty the eyes – Mess the eyes – Soil the eyes – Deflect the eyes – Escape the eyes – Shun the eyes – Muddy the eyes – Cloud the eyes – Blur the eyes – Smear the eyes -Dishonor the eyes – Affront the eyes – Malign the eyes – Slander the eyes – Tarnish the eyes – Stain the eyes – Blacken the eyes – Smoke the eyes – Alter the eyes – Liquidate the eyes – Annihilate the eyes – Wipe out the eyes – Silence the eyes – Quieten the eyes – Hide the eyes – Conceal the eyes – Rip out the eyes – Tear the eyes – Rend the eyes – Maim the eyes – Mutilate the eyes – Cripple the eyes – Reduce the eyes – Undo the eyes – Shoot down the eyes – Take down the eyes – Bring down the eyes – Disband the eyes – Dismantle the eyes – Crumble the eyes – Break the eyes – Crack the eyes – Wreck the eyes – Trash the eyes – Burn the eyes – Burn down the eyes – Burn off the eyes – Cut the eyes – Split the eyes – Cleave the eyes – Drill the eyes – Punch the eyes – Pierce the eyes – Cancel the eyes – Erase the eyes – Violate the eyes – Disappearing eyes – Evict the eyes – Assault the eyes – Usurp the eyes – Snatch the eyes – Darken the eyes – Deface the eyes – Destroy the eyes – Tear down the eyes – Strike the eyes – Injure the eyes – Uproot the eyes – Lacerate the eyes – Torture the eyes – Kidnap the eyes – Exile the eyes – Abduct the eyes – Crush the eyes…

The works for Fragments were growing, adding layers.

I worked with a Colombian singer, La mujer cabra (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7rhoxmPdZ90), with whom we composed a song based on the facts, the testimonies, which she sings with great power.

I needed to end on a high note, with a song that was like a revolt, that would accumulate the rage to transform the song. The song closes the main installation, the one that will be in the large room of Fragments. It is the first time I’ve worked with a song in this way. In the work, there will be other small songs, which function as the verses of a Greek chorus; they are women, they are the ones who predict, who lament, who make us see.

I am working on this work now.

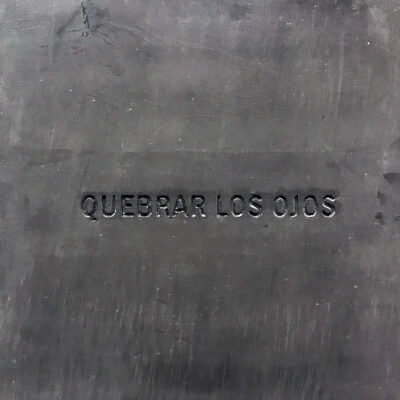

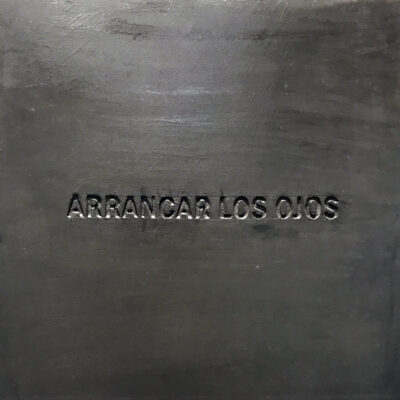

Then, I made the cement plaques with the infinite ways of saying “tears out the eyes” (I showed this at ARTBO, the art fair of Bogotá).

- Of the eyes that move sheltered by his fury | De los ojos que se mueven amparados por su furia, 2022 -2023 20 Low relief writings on wood plate covered with micro-cement Dimensions 50 x 50 cm

- Of the eyes that move sheltered by his fury | De los ojos que se mueven amparados por su furia, 2022 -2023 20 Low relief writings on wood plate covered with micro-cement Dimensions 50 x 50 cm

During this process, the Sharjah Biennial invitation came up.

I told Hoor Al Qasimi, curator of the Biennial, President of the Sharjah Art Foundation, about the project I was working on, and she was very excited about the possibility of presenting it at the Biennial. She had been in the streets of Santiago de Chile during the protests.

I told her about my idea of making holes in the ground – I had never told anyone about this idea; I thought it would never be possible (now I think I probably told her about it because during our conversation I suggested that maybe it was possible).

Holes in the earth for the plucked-out eyes to rest before returning to the bodies. Can these eyes return? Can the memory of what these eyes saw be restored?

A week after our conversation, I received an email from the Biennial, a photo of a hole in the ground, in the desert, a hole as I had imagined.

And then, we worked on deciding the quantity, size, depth, and location of the holes. We dug 16 holes, 3, 2, 1.5 meters in diameter, of varying depths, the maximum 3 meters deep. Next to the holes were a lot of dead trees; next to them was an old cemetery.

- El secreto de la tierra / The secret of the earth 16 holes in the earth Sharjah Biennial 15, Sheikh Khalid Bin Mohammed Farm, Al Dhaid, 2023. Supported by Sharjah Art Foundation.

- El secreto de la tierra / The secret of the earth 16 holes in the earth Sharjah Biennial 15, Sheikh Khalid Bin Mohammed Farm, Al Dhaid, 2023. Supported by Sharjah Art Foundation.

With Hoor, we thought that it would be nice to present – in an abandoned shed, near the holes – some audiovisual documentation: archival images of the context in which this was happening.

They transformed the shed into a small exhibition room, and I transformed the documentation video into a 29′ video: a prelude to the Fragments exhibition.

The video is called Broken Eyes.

- Broken Eyes. 2023 Full HD video, color and stereo sound Produced by Hans Nefkins Foundation, Barcelona. Courtesy of the artist

- Broken Eyes. 2023 Full HD video, color and stereo sound Produced by Hans Nefkins Foundation, Barcelona. Courtesy of the artist

But the bodies were missing. Bodies were needed to activate these holes in the ground. So, I decided to make a performance. A performance (Tear out the eyes) for 16 holes in the ground, with 18 performers, 2 percussionists, 4 announcers, 4 speakers and 5 megaphones. A performance in Arabic, English, French and Spanish.

- Tear Out the Eyes 2023. Performance view: Sharjah Biennial 15, Sheikh Khalid Bin Mohammed Farm, Al Dhaid, 2023. Supported by Sharjah Art Foundation. Photo: Motaz Mawid

- Tear Out the Eyes 2023. Performance view: Sharjah Biennial 15, Sheikh Khalid Bin Mohammed Farm, Al Dhaid, 2023. Supported by Sharjah Art Foundation. Photo: Motaz Mawid

A flashlight indicates the beginning: what I called ‘the battlefield’.

The performers wore miner’s lights on their foreheads.

Inside the holes there was a light – the light of the earth.

It took place just as the sun was setting, with extensive chronologies of events happening between 2018 and 2022 in Hong Kong, France, Chile, and Colombia coolly listed by professional speakers.

With medical texts describing in detail what happens when the eyeball explodes. With a third-person account of one particular case: Sara’s.

Circulating between the holes were the performers, questioning the audience that followed them in their walk and that sat next to them at the edges of the holes.

With an endless list of ways of saying Arrancar los ojos, said until they could say it no more, looking into the depths of the holes in the earth. With songs, with songs as echoes, with songs that burst through the audience, and upset some order of circulation. With two Emirati musicians beating on their traditional drums, in each intervention more slowly, like bodies falling to the action of the guns. In the end I sang. I, someone who doesn’t sing, sang a litany, and then others sang, in other languages, from different parts of the field. In the air, everything was pure emotion. The audience approached the performers silently, who spoke or sang without microphones, between the perforations, the holes. They moved from one place to another, not knowing what would happen, but knowing that they had to listen, they had to be close. It was like a moment of communion between so much violence named in the texts. Those who did not know about these events, began to know. Those who did recognize them were moved. Some could not stand it: those who had experienced violence on their bodies and on their families.

Then we arranged ourselves at the edge of the largest hole. The lights of the foreheads were turned off. There were a few minutes of silence; the “battlefield” became pure emotion.

AG: Thank you for this account, for this moving description. I feel that, in a way, I was there. I saw some images, which I found absolutely disturbing. I heard the voices in some of the videos you shared with me. But your story, which reconstructs both the place from which you conceived the work and what happened when you were able to do it, puts us – me and those who read this interview – in contact with the delayed time, full of perceptions, texts, voices, superimpositions that make the story of an event – someone who lost his eyes due to repressive action ordered by the State – an intelligible and, at the same time, opaque texture. How to evoke, how to translate, how to produce contact with these tremendous facts, which undermine the status of humanity? Before asking you about other works in the biennial, I would like you to tell us how you understand the poetic and political operations that art can produce to refer to such disturbing facts. I imagine that, besides asking yourself how certain things happen, you want to communicate, in a specific way, a possible register of the experience of this collective and global tragedy.

GG: This is the big question. What to do with these images? What to do with these facts? What to do with the words, the stories and the trust of the victims. What is my place. I am very careful with this. I think a lot about what images to use, how to work with the files, where to get the files from, how to manipulate them, what to see? What is it going to look like? What happens if I slow down the images if I change or remove the color. What does this operation produce? Are these images too violent? So violent that you can’t look at them? Too beautiful?

And, fundamentally, working with people, how do I relate to them? What do I offer them? Do I simplify their stories? Can I cut down their stories in editing? When I cut down a sentence, when I edit, how do I place myself in that place of power? Maybe, I decide not to cut down a sentence, because I don’t want to be in that place. I want to share that space, to register, and just be that link.

In some cases, the victims of ocular trauma entrusted me with some very personal or very precise things. For example, the badge number of the person who shot them, or the name. We then discussed this. I could not afford to put someone at risk just to show an artwork. To be aware of this together, to take the risk together with others and not to move forward alone.

All this to tell you how many questions arise from making a project like this. How many operations are made? How many decisions have to be made?

I can never move forward alone; this is a project that I came up with and made together with all the voices that speak, the images that are seen, the encounters. It sounds romantic, perhaps, but I think that the work can never be above the people, their stories, their desires, and the trust they place in me when they believe that this project – in other cases there were other projects – can help to change something, to reveal what is happening. Which images are going to coexist? How are they going to be combined? How are they going to be seen?

For example, in Fragmentos – the space where I’m going to present the work in Bogota – I’m going to work in two rooms: one very large and very spectacular, and the other smaller. In the larger one, there will be a 4-channel installation, with many images, many sounds, different resources. At first, the interviews were going to be there, as part of this big installation; I didn’t care if the work had a very long duration; I didn’t care if it lasted 4 hours. But then I thought about it more deeply. I wanted – I needed – the interviews to be heard well, to be seen well; I needed a space of intimacy for this. So, I decided, in room 1, which is the smallest room, to set up all the interviews, to add benches so that people could sit quietly and listen, so that they could take their time. The idea is to create a space of respect, calm and listening. I think it is very important to give people the opportunity to listen and be listened to.

In Sharjah, the need to propose a performance with people from there became obvious to me; it was not enough to show a video. I needed to occupy with bodies, and I also needed to be there with the others. I needed to generate that collective dynamic of moving from one place to another, of accompanied listening, of interpellation. To be there, to really be there, to be part of it at the same time as others.

In the video, my position is much safer: I do it, I install it somewhere and it works, I am there but I am not there; I peek when people look; I try to perceive reactions, but it is quite different.

For some things, in some situations I want to put bodies, live emotions, songs, things that I don’t know how they are going to happen, uncertainties (until an hour before the performance I didn’t know if I was going to dare to sing, I didn’t know how people would react). Would they stay, would they accompany me, would they come closer to listen?

I have the possibility of enunciating by occupying spaces, and I have the possibility of being listened to: this is immense. Therefore, I have a lot of poetic/political responsibility and a duty of care towards those who or from whom we build this.

AG: It is poignant to imagine the circumstances and the decisions that are made according to each space. I do believe that art involved with politics must incorporate, as a central, constant element, ethics, because, in the end, one is capturing an event that compromises the lives of others, the affections around the irreparable, and the measure of the sacrifice made in the protest, when, above all, the Chilean Constitution that resulted from the protest was not finally approved by the citizenry. The question remains as to the dimension of the sacrifice and its results. When I write, when I curate an exhibition on human rights or projects that involve people who do not belong to the art world, I am very careful about the limits of what is shown and how it is shown. How to approach from a distance that implies respect? It is a complex issue and leads to much thought.

I would like to ask you about other Latin American artists at the Sharjah Biennial. I saw Doris Salcedo, with an impressive installation on migration: Aline Motta and Joiri Minaya. But I don’t know if there were any other Latin American artists. And I would also like you to refer to artists from Eastern Europe, since we are currently working on a project called Narrating Feminisms. Eastern Europe and Latin America, with Professor Agata Jakubowska, from the University of Warsaw and academics from EE and LA. I would like to have, in your own words, a vision of the works that were exhibited.

GG: I think all art engages with a context in some way; it decides to penetrate there; it decides whether to be part of it or to stay on the sidelines. I am late in writing this because I was going to tell you all art gets involved with politics; therefore, I wondered if saying politics is saying a lot but, at the same time. saying nothing. Then, I thought about the context, the logics of survival, in what happens, in the way we constitute ourselves as political subjects. Perhaps, then it is associated with the political and not with politics. I never agreed with the concept of “political art”.

I think ethics is fundamental as a central element. It is from ethics that all actions, ways of doing, of saying, of building with others, of thinking and activating will be delineated.

Regarding the participation of Latin American artists. First, I would like to tell you that the curators decided not to indicate the nationality of the artists. It is a very radical decision, and I welcome it. That’s why I can’t know for sure who they are or where they come from. Of course, there are always clues that make it easier for us to recognize them, but they are only clues.

From Latin America, if I’m not mistaken, all the artists were women. The Biennial includes a lot of photojournalism; most of the Latin American artists come from there. For example, the first three in the list I am enclosing.

Anita Pouchard Serra, Argentina

Angela Ponce, Peru

Marisol Mendez, Bolivia

Aline Motta, Brazil

Joiri Minaya, Dominica

Flavia Gandolfo, Peru

Carolina Caycedo, Colombia

Doris Salcedo, Colombia

Coco Fusco, Cuba

Laura Huertas Millán, Colombia

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Cuba

As for the Eastern countries, although I may have missed someone, these are the artists that I now remember:

Saodat Ismailova, Uzbekistan

Aziza Shadenova, Uzbekistan

Almagul Menlibayeva, Kazakhstan

AG: Gabriela Golder is an artist of the image and the word. I am fascinated by the deep conversations we have about her work, about the relationship between art, activism, social classes, work, women. I am as moved to share these conversations as I am to walk with her in the huge marches that take place in Buenos Aires on each day of struggle for women’s rights, every March 8th (8M) or on each anniversary of the coup d’état of the last military dictatorship in Argentina, every March 24 (24M) since the return of democracy in Argentina. We share the movement of permanent questioning.