Strategies of women artists: Leonora Carrington and Female friendship

When faced with the presentation “strategies of women artists” I could not help but think of Leonora Carrington’s friendship with other women artists, how they helped each other through difficult periods and inspired one another creatively and artistically.

The idea of female friendship adopted in this text is based on research by Marilda Ionta, a researcher whose thesis was supervised by Margareth Rago, an important feminist historian from Brazil and a professor in the History department at Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp). Ionta’s thesis, named “As Cores da Amizade na Escrita Epistolar de Anita Malfatti, Oneyda Alvarenga, Henriqueta Lisboa e Mário De Andrade” [The colors of friendship in the epistolary writing of Anita Malfatti, Oneyda Alvarenga, Henriqueta Lisboa, and Mario de Andrade] analyses the construction of female subjectivation in “minor” spaces – i.e., rather than grand institutional areas. In it, Ionta comments on how Western philosophical tradition, from Plato, Aristotle, Montaigne, and Kant, to name only a few, disregarded women’s capacities for forging any form of a true relationship with others and even less among themselves. As an example, Ionta cites Aristotle’s conception: “For Aristotle, for example, women do not exert friendship in its plenitude, for they and effeminate men are drawn to lamentations, and their relationships with others derive from afflictive situations and sadness. That departs them from the true friendship” (Ionta, 2004:9).

According to Ionta, said philosophical traditions were widely spread in the Western social imaginary. The author also defines the axis of these beliefs around three main points: first, friendship is a concern exclusively of men; second, women are incapable of friendship for they only think of romantic love; third, in pre-modern societies, the sexual polarity is irreparable, whereas in industrial societies friendship between the sexes must fall under suspicion (Ionta, 2004).

Considering that such beliefs thought so highly of the importance of friendship in forging ethical citizens, the incapacity of women to do so indicated a lesser possibility of building an ethical life and citizenship. Thus, according to this conception, of also becoming a subject[1].

That said, this text considers that the friendships cultivated by Leonora Carrington were her way of growing and maturing both artistically and personally, as well as were part of her processes of subjectification[2] and counterconduct[3], to cite two of Michel Foucault’s concepts. In addition, they were also significant to the feminist consciousness – to quote Whitney Chadwick (1986) – that permeated her work.

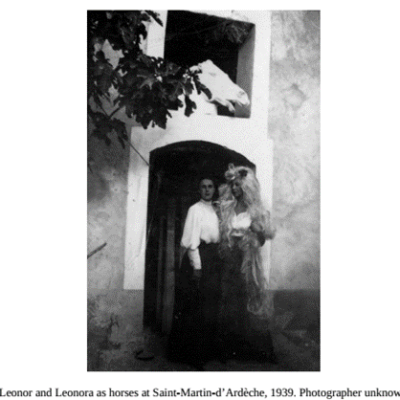

Chronologically, I would like to commence with Leonora Carrington (England, 1917-2011) and Leonor Fini’s (Buenos Aires, 1907-1996) friendship, which strengthened while Carrington was living with Max Ernst in France and continued later when the Nazi government took him. Having met in Paris in 1938, they developed a close relationship whereby Carrington admired Fini’s autonomous and exuberant way of living and her creative mind, while Fini enjoyed Carrington’s youth, vivacity, and rebellious spirit (Chadwick, 2017). Hence, it is easy to notice how both women shared admiration and drew inspiration from one another. Their friendship encompassed the sharing of creative ideas, the development of artistic work, as well as the sharing of anguishes related to the Second World War and the sufferings that Carrington experienced because of it.

Regarding their creative companionship, Chadwick (2017) analyses how dreams Carrington shared with Fini in letters became paintings by the latter, just as some of the costumes and theatrical settings by Fini constantly appeared in Carrington’s paintings and writings. The remarkable influence of one in the other’s work can be seen in the following examples:

First, the paintings From one day to another I and II, from 1938, were greatly inspired by a dream Carrington shared with Fini in letters.

- Leonor Fini, From one day to another I, 1938

- Leonor Fini, From one day to another II, 1938

Additionally, there is the painting of a theatrical scene that places a Leonora Carrington-like figure as the main character and warrior, as in The Alcove: an interior with three figures, from 1939. Concerning this painting, Giulia Ingarao (2018) notices how Fini represents Carrington as a warrior in her posture and firmness, rather than in acts of violence and power.

- Leonor Fini, The Alcove: an interior with three figures, 1939. Oil on canvas

- Leonora Carrington, Portrait of Max Ernst, 1938

As for Portrait of Max Ernst, painted by Carrington in 1938, several elements in the image were drawn from Fini’s theatrical settings.

But, most of all, what is imperative to emphasize is how Fini helped Carrington emotionally, pushing her to express her emotions creatively, whether they were repulsion, hatred, fear, despair, or concerns about losing her mind. Whether intentionally or not, Fini eventually encouraged working through of trauma and, in that process, helped her retain (most of) her sanity. The emphasis on “most of” refers to the notion that in traumatic situations the concept of sanity becomes fragile and questionable.

As for this specific issue, it is well-known that the period of intense military activity, loneliness, and the anxiety that arises from this sort of conflict left Carrington deeply wounded emotionally. Her partner had been taken away to a concentration camp, and she was a young foreigner, alone in a small village where people knew her and Ernst’s situation – some even tried to denounce them. When things deteriorated in France and her situation worsened, Carrington left for Spain.

In Spain, she noticed Madrid was sick, as was she. After meeting a man, whom she identified as a Nazi, and being violated by officials, she decided to call the British council to denounce them. Those actions led to her incarceration in a Spanish sanatorium for several months (approximately six). When she was released from this asylum, just to be conducted to another one in South Africa, she fled, called a friend, and left for New York and then Mexico.

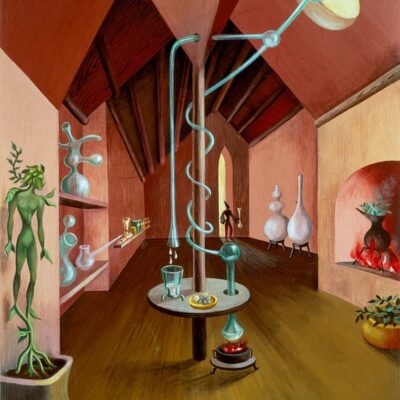

When exiled in Mexico, Carrington met Remedios Varo and Kati Horna, who had also been exiled, and developed a close friendship in their domestic realm, especially in the kitchen, where they elaborated on spells, worked on alchemic processes, and explored their creativity. The “new museum for women artists” website[4] comments that Carrington believed meeting Varo changed her life. Their friendship traversed maternity, domestic life, and artistic creation. As Joanna Moorhead (2017) puts it, many of their experiments and conversations would later become paintings and photographs.

There are examples such as The old maids by Carrington and Laboratorio by Varo, both from 1947. In both paintings, the kitchen-laboratory is the main motif, and both show their views on this setting that became their preferred place to share their lives together.

- Leonora Carrington, The old maids, 1947

- Remedios Varo, Laboratorio, 1947

Another pair of similar works is Syssigy, by Carrington and El Sastre de señoras, by Varo, both from 1957, where a sort of mystical meeting takes place. Besides the thematic approach, there are also some formal resemblances: framework, disposition of figures, angles, etc.

- Leonora Carrington, Sissisy, 1957

- Remedios Varo, El sastre de señoras, 1957

However, it is relevant to notice that according to Stefan van Raay “Carrington’s work is about tone and color and Varo’s is about line and form”. Raay suggests that however close they and their themes were, both still held their individualities in their approaches to art.

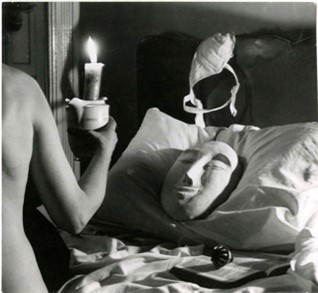

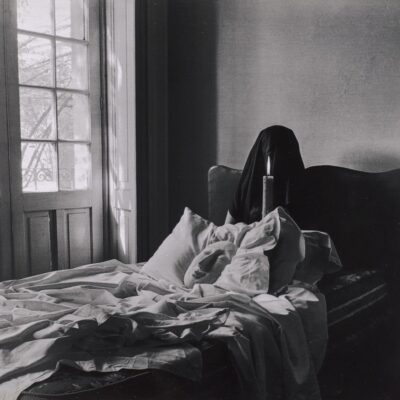

As for Kati Horna, they collaborated on the series “Ode to necrophilia” by Horna, from 1962, where the two of them came up with the concept and Carrington modelled for Horna’s pictures.

- Kati Horna, Ode to Necrophilia, 1962

- Kati Horna, Ode to Necrophilia, 1962. Source: https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/134436

So, this text aims to discuss how Carrington’s friendships with other women artists were strategies she developed to remain creative, inventive, and active, while also feeding her beliefs about the necessity of building strong female bonds and strong repertoires of feminine creativity.

It is also relevant to highlight, as in Mercedes Fuente’s text, that Carrington was more a feminist than a Surrealist since she insisted on making her path into surrealism, not by association with the great men of this style – Freud, Breton, and others – but by herself, her symbolic references, her exploration of her own psyche and her experiences of the feminine (friendship, Celtic heritage, motherhood). In addition, it is relevant to mention that Carrington and Varo were among the first artists in their surrealist circle to disentangle from masculine references to creativity, developing their own imagistic language, associated with their needs as women.

To finish, I would like to cite this excerpt by Fuente that wonderfully summarizes the goal of this analysis:

“Chadwick believes that Carrington’s originality relies on a feminist consciousness that already shows in her early artworks, but that starts to be done more evidently in the 40s in Mexico, from her maternity and also for her friendship with other women, especially with Remedios Varo, with whom she shares techniques and pictorial themes (in which are included the importance of domestic activities, the kitchen – a form of alchemy), as well as a female fraternity that is also a characteristic of women linked to surrealism” (Fuente, 2016:157).

By: Ana Carolina Salvi

References:

CARRINGTON, Leonora. Down Below. New York: New York Review Books, 2017.

CHADWICK, Whitney. The militant muse: love, war and the women of surrealism. London: Thames and Hudson, 2017.

CHADWICK, Whitney. Leonora Carrington: Evolution of a Feminist Consciousness. Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Spring – Summer), pp. 37-42, 1986.

COLVILE, Georgiana. Beauty and/Is the beast: animal symbology in the work of Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Leonor Fini. In: Surrealism and women. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991.

FUENTE, Merdeces. La joven leonora carrington y el movimiento surrealista. 1616: Anuario de Literatura Comparada, n. 6, 149-170, 2016.

INGARAO, Giulia. “The Alcove: an interior with three figures”: Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst e Leonor Fini – Saint Martin d’Ardèche 1938/1940. Predella journal of visual arts, n°41-42, 2018.

IONTA, Marilda. As cores da amizade na escrita epistolar de anita malfatti, oneyda alvarenga, henriqueta lisboa e mário de andrade. Tese (Doutorado em História) – Unicamp, 2004.

MASIUS, Megan. Artist Friendships: Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo. In: https://nmwa.org/blog/artist-spotlight/artist-friendships-leonora-carrington-and-remedios-varo/, 2017.

TELLES, Norma. Belas e feras. In: https://www.normatelles.com.br/belas_e_feras/, 2006.

TELLES, Norma. Anjos da anarquia. In: https://www.normatelles.com.br/anjos_da_anarquia/, 2010.

[1] To become a subject is a Foucauldian concept. You can see an example of its use here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30036154#metadata_info_tab_contents

[2] For a better understanding of “subjectification”, see: LAWLER, Leonard; NALE, John. The Cambridge Foucault Lexicon. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

[3] For a better understanding of “counterconduct”, see: LAWLER, Leonard; NALE, John. The Cambridge Foucault Lexicon. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

[4] Source: https://nmwa.org/blog/artist-spotlight/artist-friendships-leonora-carrington-and-remedios-varo/