The Importance of the Theoretical Approach of Lise Vogel

Author: Vesna Vuković

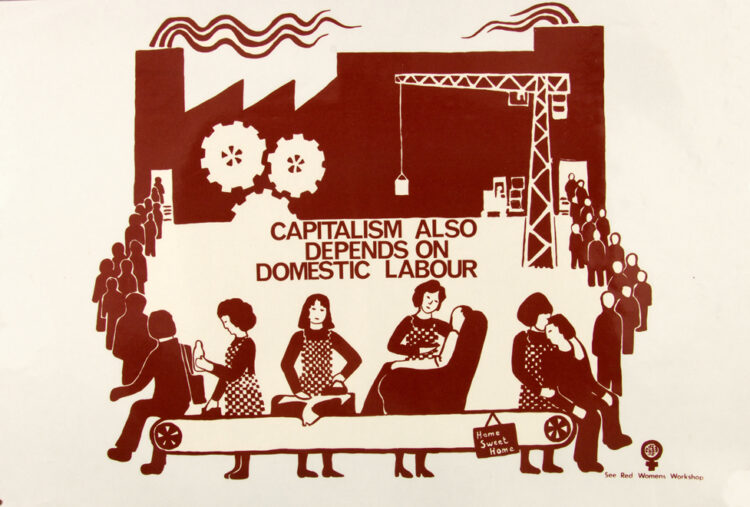

Red Women’s Workshop, A Woman’s Work Is Never Done, 1974.

The academic and political path of Lise Vogel (1938 –), a Marxist feminist, feminist sociologist, art historian and activist, is an exceptional example of the meeting of biography and history. Her scientific research was shaped and guided by political events, and activist experiences crucial for her broad theoretical approach to the issue of oppression in a capitalist society. On the other hand, historical changes had a strong impact on the reception of her work, almost as if we could read from it the trajectory of feminist and Marxist theoretical development from the 1970s to today. Her contributions to Marxist and socialist feminism are enormous, although they have not always been sufficiently recognized and acknowledged, which is most vividly illustrated by the case of the book Marxism and the Oppression of Women. Toward a unitary theory.[i] When it was published in 1983, as an intervention in the domestic labour debate among socialist feminists in the 1970s and as an attempt to find Marxist answers to open questions, it elicited almost no response.

- Lise Vogel, Marxism And Oppression Of Women, Rutgers University Press, 1983..

- Lise Vogel, Woman Questions: Essays for a Materialist Feminism, Pluto Press, 1995.

Biographical and experiential moments that guided and motivated her, but also brought her back to reconsider her own insights, Lise Vogel regularly points out in her forewords and lectures. She received her first political lessons at her parents’ home. Both her father and mother were members of the interwar left, and her mother, a communist, was a particularly important figure during her childhood. The political experience to which she owes the most was her participation in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), that is, two summers spent in the American South, in Mississippi, in 1964 and 1965. “I got far more out of being in Mississippi than I ever was able to give back,” she wrote in one place[ii]. Work with black communities, especially teaching engagement in the Freedom Schools, created as a response to educational segregation, but also the experience of anti-war demonstrations and two arrests, were decisive moments in her political maturation.

All this, as well as the experience that followed within the framework of the women’s liberation movement, was decisive in focusing her interest on researching race, class and gender – that is, the unraveling of racial, class and gender oppression. Her feminist work is therefore a living proof that second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s was a much more heterogeneous phenomenon than it seems to us from today’s perspective of its development, as its connection with the Civil rights movement and the struggle against racial segregation has been forgotten today. Namely, after the turbulent 1960s, feminism in the USA received academic recognition and institutionalization in the form of women’s studies courses and magazines in the 1970s. As Vogel testifies, while the work of feminists in the earlier phase was focused on changes in the everyday life of women, from that moment it spilled over into scientific articles and books. Younger feminists grew up without activist experience and the close connection between theory and practice that shaped Vogel and the women’s liberation movement in its early stages. It began to seem that feminist theory was a product of the white academy, and that it was there – for the academy. In parallel with this development, the ground is being prepared for the vehement appearance of neoliberalism in the late 1970s, the left lost its social position and weakened together with its political formations, which was not without consequences on the theoretical level as well. Against the spirit of the times, Vogel did not reorient herself theoretically but continued to believe in socialism and Marxism even when everyone claimed that they were dead.

Her monumental contribution to socialist and Marxist feminism in the book Marxism and the Oppression of Women went almost unnoticed for the reasons described above. The only review was written by Johanna Brenner, another socialist feminist who worked both theoretically and politically to connect the class struggle with other forms of subjugation. Departing from the literature that has traditionally dominated socialist feminists analysis, The German Ideology and The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Vogel turns to Marx’s basic categories from Capital, in order to place the problem of women’s oppression in this categorical framework, and to theorize domestic labour as an integral part of the capitalist mode of production. Not only did she respond to debates about the productivity of domestic labour and the question of whether it produces surplus value (no, domestic work produces use value, not exchange value, therefore it does not directly produce surplus value), but also with the insight that “labour power is not produced capitalistically ( …) but in a working family based on kinship” opened analysis of the family toward its structural relationship with the reproduction of capital. Moving away from the transhistorical concept of patriarchy, which focuses on the internal structure of the family, she analyzed female oppression via the Marxist concept of social reproduction. The theorists of social reproduction that gained momentum a few decades later are to be credited for the revaluation of her work and the reissue of this book after a full 30 years.

Her contribution to the feminist intervention in art history was not quantitatively large, but it is extremely important. Namely, she left the field early, her engagement in the movement for the liberation of women distanced her from her colleagues and prompted her to leave a secure academic position and the prestigious career path opened for her by the book The Pillar of Antonius Pius.[iii] She studied ancient art, standing up for new approaches and methodology and criticizing the formalism and alleged neutrality of analytical categories dominant in the discipline. In the late 1960s, she developed a thesis on the visual organization of Roman art as essentially “polyphonic”, arguing that “ways of seeing” before the Renaissance were much different and that only since the Renaissance has the work of art been approached as a whole. Abandoning the safety of the beaten academic path, she engaged in the introduction of feminist education in art, teaching one of the first courses on women and art at the Massachusetts College of Art and Boston University, and drawing guidelines for feminist intervention in the field. At a time when the feminist movement was increasingly focused on cultural issues, Vogel turned to the study of sociology, a scientific field in which she earned a second PhD and stayed for the rest of her academic career. In the end, art history remained for her a sideline, external to her intellectual and political life.

Her contributions to the discipline represent a rare phenomenon within the framework of feminist intervention in art history and second-wave, cultural feminism that has put forward the politics of difference by looking for specific female qualities, often in the sphere of art. In contrast to this view, Vogel takes a materialistic position and in her analyzes emphasizes the importance of the institution of high art with its ideological separation and social isolation. In the text “Fine Art and Feminism: The Awakening Consciousness,”[iv] she asserted that the criticism of the art establishment has not been included so far in discussions about feminism and art, which at that time mainly revolved around the issue of female aesthetics and the peculiarities of female sensibility. She criticizes liberal attempts to solve the problem of the subordinate position of women in art within the framework of capitalism, and in doing so – while acknowledging all the merits – she will not spare Linda Nochlin either, arguing that in her feminist intervention in art history she does not recognize class and racial oppression. The convergence of gender, race and class in high art is elaborated in her text “Modernism and History,”[v] focusing especially on modernist mystifications of the work of art and its isolation, and its separation of artists and viewers from their social environment.

In her theoretical work generally, she defends Marxism against the then frequent feminist attacks with the conviction that Marxist categories can be reexamined through a feminist lens, that Marxism as a research program can and must be expanded. Her attempt was interrupted by the advent of neoliberalism, “a moment propitious (…) for a disavowal of ‘grand narratives’ that was a hallmark of postmodern and poststructuralist theory,” when “striving after unitary theories of any sort was glibly dismissed as the quaint pursuit of fossilized modernists.”[vi] This builds a basis for her central theoretical and political preoccupation: her interest in the contradictions of equality, more precisely “the tensions between human heterogeneity and the notion of equality,”[vii] which permeates all her works. Debates between equality and difference are particularly important today, and Marxist answers to them are urgently needed.

Lise Vogel, Woman Questions: Essays for a Materialist Feminism, Pluto Press, 1995.

[i] Lise Vogel, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1983)

[ii] Lise Vogel, Woman Questions: Essays for a Materialist Feminism (New York: Routledge, 1995), 14.

[iii] Lise Vogel, The Column of Antonius Pius (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1973)

[iv] Lise Vogel, „Fine Arts and Feminism: The Awakening Consciousness,“ Feminist Studies, II, 1 (1974), 3–37.

[v] Lillian S. Robinson, Lise Vogel, „Modernism and History”, New Literary History, III, 1, (autumn 1971), 177–199.

[vi] Susan Ferguson, David McNally, “Capital, Labour-Power, and Gender-Relations: Introduction to the Historical Materialism Edition of Marxism and the Oppression of Women”, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2013), XXI.

[vii] Lise Vogel, Woman Questions, 18.