The matriarch of Brazilian contemporary art: Anna Maria Maiolino /PSSSIIIUUU…

Between May 7th and July 24th, a retrospective exhibition of the Italian-Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino (Scalea, IT, 1942) was held at the Tomie Ohtake Institute in São Paulo, Brazil, with the name of “PSSSIIIUUU…”, an ambiguous onomatopoeic word evoking silence, flirting, or a distant call. Planned for over 3 years, the anthological exhibition provided both a compilation of iconic pieces from the artist’s career, as well as a presentation of rarely exhibited works and those that had never previously been exhibited, in addition to a commissioned installation and an unprecedented performance, which took place on the last day of the exhibition.

- Views from thViews from the exhibition “PSSSIIIUUU…” Pictures from Talita Trizoli. May 2022e exhibition “PSSSIIIUUU…” Pictures from Talita Trizoli. May 2022

- Views frViews from the exhibition “PSSSIIIUUU…” Pictures from Talita Trizoli. May 2022om the exhibition “PSSSIIIUUU…” Pictures from Talita Trizoli. May 2022

Born in Italy to a Calabrian father and an Ecuadorian mother, Maiolino is the youngest of ten children, a condition that earned her both affectionate attention from her family and also a need for survival strategies in the face of not only the parental effervescence of a big family, but also because of her life situation: being an immigrant is inherent in her subjectivation, since she migrated with her whole family in 1954 to Venezuela due to the economic crisis in Italy. She began her artistic studies at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas Cristóbal Rojas in 1958 and then migrated one more time – to Brazil – to the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1960, where she finished her training at the School of Fine Arts of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (EBA-UFRJ) in engraving.

- Views from the exhibition “PSSSIIIUUU…” Pictures from Talita Trizoli. May 2022

Currently, the artist occupies a symbolic-affective place in the imagination of a recent generation of young artists, as an example of career management and varied use of languages, without losing the coherence of poetic research, thus being elevated to the position of matriarch of Brazilian contemporary art. The term matriarch is used for her precisely because of the affective and psychoanalytic dimension of her production, which deals with amorous, domestic, erotic, cartographic, and political issues simultaneously in an assertive and affable way, but with deep control of the chosen formal elements.

- Views from the exhibition “PSSSIIIUUU…” Pictures from Talita Trizoli. May 2022

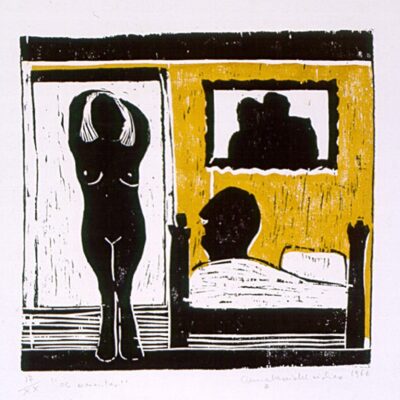

The drawings and engravings are the most singular and curious works in the show as they are pieces from the beginning of the artist’s career – mostly unseen – since Maiolino is currently most valued in the commercial circuit for her installations and sculptural works and for her conceptual production from the 1970s. Works such as “My family” (1966), “The hero” (also from 1966 and now in the MASP collection), and “Glu… Glu…” (1967) are some of the best known of her xylographs and paintings. However, what draws our attention are works such as the painting “Kehm” (1967), the xylograph “The Lovers” (1966), and the cartoon-like drawings from the series “Between Pausas”, (1968-1969). This is not because of the evident use of the formal solutions of pop art, but because they corroborate a suspicion of art history researchers: that Maiolino was one of the few artists of her generation to focus on the theme of love, family, and maternal relationships without hesitation.

- Ana Maria Maiolino, “My Family”, 1966

- Ana Maria Maiolino, “The hero”, 1966/2000

- Ana Maria Maiolino “Glu… Glu…”, 1967

- Ana Maria Maiolino, “KEHM”, 1967

- Ana Maria Maiolino, “The Lovers”, 1966

- Ana Maria Maiolino, from the series “Entre Pausas (Between Pauses)’, 1968-69

- Ana Maria Maiolino, from the series “Entre Pausas (Between Pauses)’, 1968-69

Such themes in the Brazilian art scene of the 1960s and 70s were not something recurrent, especially in the case of female artists, because of the stigma of feminine art that devalued the quality of the works of women artists. It is worth remembering that the arrival of feminist politics in Brazil occurred in a skewed way, either because of the civil-military dictatorship, or because of class and race prejudices, crystallized in the social strata of this generation of artists. Therefore, this production by Maiolino requires fresh analysis, not only because of her bittersweet dedication to themes of family intimacy, but also because of the low circulation of these works in other collective or individual exhibitions of the artist, a symptom of the resistance of the art world to dealing with the themes of motherhood, romantic-love, and affective frustrations (at least from the female perspective, since male artists have approached such issues systematically throughout the history of art, but often with a moralizing and patriarchal bias).

Although the presence of these works was a pleasant surprise at the show, this was by no means the curatorial scope of the person responsible for the clipping, the curator Paulo Myiada, the institution’s artistic director, who chose to display the main lines of the artist’s production, which completed 80 years in 2022. The refined assembly of the pieces throughout all three rooms on the first floor of the institute was a statement of the importance of Maiolino to the circuit, since the only individual exhibitions that had previously been presented were those of Louise Bourgeois in 2011 and that of Yayoi Kusama in 2014. Furthermore, the selection of the pieces was a harmonious presentation of the technical, formal, and thematic variety that had crossed Maiolino’s artistic interests throughout her career.

The only caveat regarding the expography are the two reenacted pieces from the intervention carried out by the artist in the experimental collective Mitos Vadios in 1978, held in a parking lot on Rua Augusta, one of the youngest popular addresses at the time, with expensive restaurants and luxury stores. One of these pieces were two bags of beans and rice, grains commonly used in Brazilian eating habits, tied by a black satin ribbon with a bow, placed on a pedestal with black fabric, and the second was a clothesline which held different kinds of toilet paper, fixed to a white mobile wall, in which there is a growing line of this hygienic object that indicates a social scale, stabilized by the quality of the materials: from the most precarious and rough to the most soft and fragrant. Those are two pieces that comment on the state of misery and hunger of the population in 1978 due to the economic and political crisis triggered by the military dictatorship, a condition that has been cyclically repeated in the country since 2016, which reinserted Brazil into the world hunger map.

- Anna Maria Maiolino, “Mitos Vadios”, 1978/2022

- Anna Maria Maiolino, “Mitos Vadios”, 1978/2022

Due to the ephemeral and political nature of these two works, both were lost in the expographic composition, displaced from the rest of the show, because they were not integrated into the white cube of the galleries, but rather occupying a Lounge in the Tomie Ohtake Institute building, in which the architecture of Ruy Ohtake, author of the building project and son of the artist who names the cultural space, obliterated the subtlety of the political and material criticism proposed by the artist.

- Anna Maria Maiolino, “Solitary or Patience”, 1976

In any case, Maiolino’s show was not just a caress in an art scene that had already lost interest in the production of women artists and feminist issues (although Maiolino does not understand herself as a feminist) in favor of other social agendas that are captured by the machinery of capital, but it was a show that potentiated critical-political possibilities, at a time when contemporary Brazilian production left aside the metaphorical and allegorical dimension present in materials and forms, and became increasingly literal.

By: Dra Talita Trizoli