Aging and Images of Youth: Yente’s Collages

Author: Ayelen Pagnanelli

Yente was born Eugenia Crenovich in 1905 in Buenos Aires, Argentina from a well-off Jewish Ukrainian immigrant family. Yente was her nickname, which she used as her artistic name throughout her life. Primarily known for her investigations into geometric abstraction in Buenos Aires, in the 1960s, Yente spent time in Northern Italy where she produced a body of mixed media works. Through the use of magazines, advertisements, wrappers, letters, ink and paint, the artist incorporated highly fragmented images of female bodies where the artist wrestled the tensions between an aging body and the cult of youth, between Genova and Buenos Aires as well as abstraction and figuration.

Yente had some relatives in Chile, which is why she had been in Santiago de Chile since 1933 training as an artist as well as studying philosophy at the University of Buenos Aires. Already in 1934 and 1936, Yente received awards at art salons for her early figurative artworks; unfortunately, only a few examples of her work from this time remain. In an artist studio in the city of Buenos Aires in 1937, the young artist had one of her first encounters with –the then controversial artist Juan Del Prete, who had recently arrived from a long stay in Europe and would become her husband and life partner. Del Prete was born in Vasto, in the Italian region of Abruzzo on the Adriatic coast in 1897, and when he was just a few years old he emigrated with his family to Argentina. He took his first steps in art from the Buenos Aires neighborhood of La Boca and thanks to the support of Amigos del Arte he traveled to Paris in 1930, where he began to explore abstraction. Upon his return, he exhibited non-figurative works in two exhibitions in Buenos Aires, causing significant negative criticism but becoming emblematic of the history of Argentine art.

By the time they met, Yente and Del Prete were actively participating in the Buenos Aires artistic milieu and exhibiting. This encounter was a turning point in Yente’s life and in her practice, as she embraced abstraction from then onwards. As a couple, they decided to destroy almost all the figurative works on paper that Yente had produced in recent years. With this destructive act, Yente began a creative path of exploration of abstract languages. Yente’s works from that year, 1937, give an account of the radical shift in her production. Las muchachas[1], a medium format tempera on paper, weaves together figuration with the exploration of abstraction. The figure has not disappeared: in this composition, two women are at the center. Yente presents the young women as united, with their hands raised. The face of the central figure is superimposed;however, on the left side of her face, a pink plane outlines a third face. This shape, in a darker value, is repeated in the second figure but there it does not build an additional face, but generates volume instead, which Yente replicates in her arms in the foreground. Curved forms create part of the clothing of the figures and towards the center of the work they stop referring to the figures altogether, becoming only colored planes. The background echoes those shapes and colors, conjugating geometry with organic forms, and combining colors in one of her first forays into abstraction.

From the late 1930s until the late 1950s, Yente made work in a wide variety of media including drawings, paintings, tapestries, sculptures in celotex (a material derived from sugar cane), and artist books. In fact, Yente was the first woman to have a solo exhibition of her abstract paintings in Argentina’s capital in 1945; at a moment when other, younger artists, were only beginning to explore the possibilities of abstraction. Some of her tapestries, such as number 6[2], made in 1958, enter a dialogue with art informel; this detail shows how Yente carefully combined satin stitch embroidery with painting on the fabric in this more organic, abstract composition, reminiscent of the new, gestural modes for producing paintings. Yente became known for these pioneering abstract artworks, which grabbed the most critical, curatorial and academic attention. Throughout Yente’s and Del Prete’s lifetime it was Del Prete who was the more recognized artist. Since 2009 that tendency reverted, when Yente had an exhibition at MALBA, the Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires that paired her works with those of Lidy Prati, another woman artist who was a key figure in Argentine abstraction in the 1940s and 1950s who had been overshadowed by her husband, the artist Tomás Maldonado. Yente then had a book critically examining her oeuvre, another reprinting some of her critical writings, and then in 2019, MALBA yet again held a major exhibition showcasing her lifetime works alongside Del Prete’s.

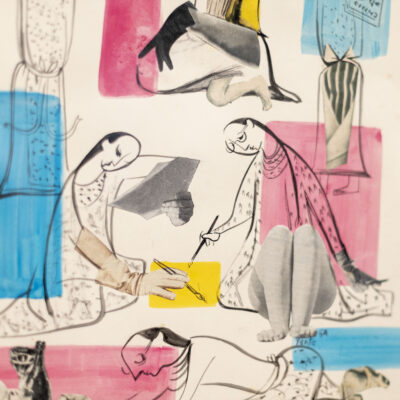

Yente has produced works on paper since the beginning of her career. There are some examples of collages already from the 1950s in which she was ironizing upon a local art critic, with a background with a geometric abstract composition, over which Yente collaged images of male bodies in which she combined ink lines, echoing Persian miniatures where the critic appears as a preacher. However, her collage and assemblage production shifted in the following decade.

In her sixties, Yente lived for long periods of time in Genova. Her husband, Juan Del Prete had retired from his day job and they decided to spend the Southern hemisphere winters enjoying the Italian summer as well as making art. As mentioned earlier, he was originally Italian and still had some family so they stayed near them. Del Prete had a studio, while Yente had to work on bedside tables where she produced her collages. In fact, Yente made works with Del Prete’s discarded materials such as matches. These difficult material conditions under which she made these series of collages have been discussed, more recently in their gendered inequality. However, the large body of work Yente produced has been under-analyzed.

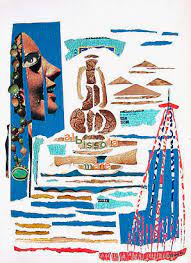

In the collage titled Abissola, a lovely memoir of the town, Yente made use of what seem to be candy wrappers as well as images from magazine advertisements. Just like in the 1951 collage, The teacher’s lesson, Yente constructed the composition with thin rectangles of colors on the white surface. In addition to the boat (represented in a minimal effort) and the incorporation of words, Yente here included a female face. On a light blue background, the young woman’s face seems to have been taken from one photograph and sliced, an oversized eye from a different image placed on top, to its left, a necklace with green and brownish stones. Three elements of this face stand out. First, the fact that this is a woman’s face; second, that this is a young woman, and third, that it is highly fragmented. While making this series of collages, Yente was faced with a sudden flood of images of young women in the media, likely more than those she would have encountered in Buenos Aires, and so she critically put these images into question through the use of collage. Indeed, it was in the 1960s that Yente begins to incorporate women’s bodies more consistently into her collages. Yente exercised a reflection on the body, or perhaps on the body’s image, through this meticulous fragmentation and rearticulation of the young female body in tension with her own experience of femininity. Perhaps, one could even imagine her reflecting on how different the experience of being a young woman in the 60s was when compared with the 30s.

- Yente, Albissola, 1963, collage, papers and wood on board, 49,5 x 34 cm.

- Yente, La lección del maestro (The teacher’s lesson), 1951, collage, 49,2 x 35,6 cm.

Yente had long included religious themes in her artworks and artist’s books. So it is no surprise that they appear in her collages. In Donne nella Basilica, the fragmented bodies of women appear mixed within the depiction of the Basilica itself. There isn’t any male or religious imagery aside from the flying doves in the top right corner. Yente incorporated fabric into the collage, a practice she would pursue further in the years to come. Being of Jewish origin herself, but not practicing, she made artists books for her nieces (Yente never had any children) on religious themes, and included many in her travel-related ones. She was a vegetarian and read eastern philosophies and religions, though quite evidently incorporated catholic imagery into her visual world during her time in Italy. She was plainly interested in religiosity, and in this collage we can appreciate how she used to observe Catholicism.

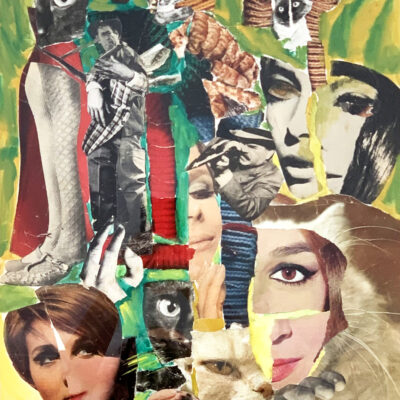

In La caccia, another collage made a few years later, Yente exacerbates this exploration of the young female body. The fragmentation of the bodies accentuates a sensation of anonymity, of the generic female model, a sense of the disposable, of the replaceability of these women. The woman on the lower left has a haircut shared by the images of two women. Women’s faces, legs, and hands are scattered throughout the composition alongside fragmented images of cats. Could this be a play on words between “cat eye” makeup and the felines? Are these womens on the hunt? Or are the men hunting them as the image of a man holding a rifle might indicate? Yente appears to strain the conflicted status of young women in media and society while she herself no longer enjoys/suffers being a young woman.

- Yente, Donne nella Basilica, 1967.

- Yente, La caccia, 1967, Collage with photomontage and tempera on board, 49,9 x 35 cm.

This corpus presents a departure from the works Yente was mostly associated with (even though this is not to say that they were unknown since both Yente and Del Prete were famous for their very eclecticism). They were also made when Yente was no longer young. This fact is actually crucial, as art history seems to continue to focus on artworks made by women when they were young, reifying society’s agism. In a certain sense, Yente’s late collages highlight young women’s new opportunities in the public sphere as seen through the eyes of a woman past her youth. Thus, Yente’s reflections, translucent in these works made them all the more interesting for an intersectional feminist analysis.

[1] Yente, Las muchachas, 1937, tempera on papel, 63 x 47.5 cm.

http://cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/yente/05_obras_1937a.php

[2] Tapestry #6, 1958, wool and paint on canvas, 121 × 46.9 cm

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/401491?artist_id=131916&page=1&sov_referrer=artist