Social Reproduction and the Writing of History

Currently in Warsaw, two exhibitions are on view that focus on social reproduction and writing of women’s history. Social reproduction can be understood as work that is beyond productive work, or, as Tithi Bhattacharya explains: “the activities and institutions that are required for making life, maintaining life, and generationally replacing life. I call them life-making activities. Life-making – in the most direct sense – is giving birth. But to maintain that life, we require a whole host of other activities, such as cleaning, feeding, cooking, washing clothes.”

Thus, one of the Warsaw’s exhibitions deals with social reproduction understood as pregnancy and childbirth (labor); therefore, reproductive rights and the struggle for them. The other exhibition develops the concept of social reproduction in the direction of maintenance labor and its professionalized variant; that is, the history of Warsaw’s female servants during the interwar period.

These two shows are very different and represent different strategies of writing women’s history but besides the common main topic – social reproduction and writing women’s history – they also interweave certain details or threads, such as the topics of female body, voice, or use of fabric to create the exhibition’s architecture, but also threads related to the geography connecting Warsaw and Buenos Aires.

The first exhibition I visited was Who Will Write the History of Tears at the Museum of Modern Art. Warsaw’s MoMA – the central contemporary art museum in Poland – is run half by the City of Warsaw and half by the Ministry of Culture National Heritage and Sport: the magistrate and the government. The government in Poland is currently a conservative one, and it was the actions of this government that caused mass protests in defense of reproductive rights in recent years.

There have been many demonstrations, starting in 2016 and continuing in the following years. Mass protests from 2020 were the biggest since the 1980s in Poland. These events have already been the subject of several exhibitions organized in Poland, such as: Polish Women, Patriots, Rebels… (2017) in Arsenal, the city gallery in Poznan, curated by Izabela Kowalczyk, and You’ll Never Walk Alone (2020-2021) in the Labyrinth Gallery in Lublin, curated by Waldemar Tatarczuk.

In Warsaw’s MoMA, however, reference to recent events and the situation in Poland wasn’t straightforward; it was rather redirected towards “we give voice to the women artists” and towards the presentation of artistic strategies related to the fight for women’s reproductive rights in general, following the example of different countries and periods. The curators – Magda Lipska, Sebastian Cichocki and Łukasz Ronduda – began their text with historical distance: “For over a century debate has raged over women’s reproductive rights”. Thus, the current events in Poland and the struggle for reproductive rights became universalized in terms of time and space.

[Exhibition view Who Will Write the History of Tears; photo by Sisi Cecylia]

Was this the right strategy in the current situation? Certainly, it was the safe one. Undoubtedly, it was a bold gesture to take up such a topic in a public institution, during a time when the management of other museums and galleries were being replaced with those supported by the conservative authorities. Surprisingly in these circumstances, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw decided to take the side of women. That is why many people perceived the event as a sort of celebration – a commemoration of the recent protests and the not yet written history of women’s struggle for the reproductive rights in Poland – in which women activists from the 1990s suddenly became historic figures and heroes. I myself also enjoyed this fact and was happy to see the iconic poster by Barbara Kruger, a symbol of the first protest after transformation and the work by Anna Janczyszyn-Jaros, providing food for thought on the situation of women during the decade of the 1990s in Poland.

[Exhibition view Who Will Write the History of Tears; photo by Sisi Cecylia]

[Exhibition view Who Will Write the History of Tears; photo by Sisi Cecylia]

Their contemporary reflection is the collection of the cardboard banners from recent protests and the presentation of the initiative Public Protest Archive. Although next to the artefacts connected to Polish protests, it was decided to present works with similar overtones from different political and historical contexts (Ireland, USA), which resulted in the universalization of the topic; like, the fight for reproductive rights has been a permanent fixture in women’s history no matter where or when. However, these works showed interesting visual strategies and potential in the political power of women’s protests.

However, this above-mentioned political narrative was juxtaposed with works based on the eponymous personal experience of the women artists. These usually connected abortion with trauma and used abject aesthetics (in some cases it was not even clear if the topic was an abortion or a miscarriage). These works introduced an ahistorical narrative to the issue.

Although the film shown as the introduction to the exhibition (interviews with pro-choice activists from the 1990) pointed to the deterioration of the situation of women with the change of the political system in Poland. Presentation of works such as those by Teresa Jakubowska, described as the critique of the experience of the abortion during the People’s Republic of Poland, contradicts this narrative. Similarly, showing work by Teresa Tyszkiewicz, who performed about pregnancy (in her late fifties) in 2009 and living in France, again ignores the geopolitical context in favor of personal experience.

Thus, works by activist artists’ demanding reproductive rights, when juxtaposed with those based on women artist’s experience of abortion or pregnancy, lose their momentum and cause emotional confusion.

[Exhibition view Who Will Write the History of Tears; photo by Sisi Cecylia]

The work of the Argentinian artist Mariela Scafati also caused such confusion for me. Her monumental installation – entitled Mobilization – was the dominant work of the whole exhibition. In the curator’s description, one can read that the geometric and colorful figures are transpositions of the bodies of the artist’s friends –activists involved in the fight for women’s reproductive rights – and that the work, that is the very figures, were presented as suspended from the ceiling, or as figures on the march. So why are the figures lying in Warsaw? The curatorial text explains that the lying figures symbolize pandemic dormancy, rest before the next fight. However, contrary to the title, this work gives the impression of resignation. Unfortunately, the figures can be simply associated with the corpses of the defeated lying on the field after a lost battle.

[Exhibition view Who Will Write the History of Tears; photo by Sisi Cecylia]

Such a reception of this work is inevitable if we consider the Polish context of its presentation. Shortly before the opening of the exhibition, on November 6, 2021, on the streets of Warsaw and many other cities in Poland, people gathered to protest the death of Izabela from Pszczyna: the first victim of the new abortion restrictions. The woman was admitted to hospital with a lack of water: a defect that does not allow the fetus to be saved. However, according to new regulations, the doctors had to wait until the fetus’ heart stopped. The woman was fully aware that her life was endangered, and that this had been caused by the new law in Poland, as the content of the text messages that she had sent from the hospital to her family showed. These were later shown on a protest’s banners. The pregnant woman died from septic shock; her daughter was orphaned. Protesters in the streets marched under the slogan “Not one more”; however, only a few months later, another woman died of sepsis (Agnieszka from Częstochowa, January 26, 2022), because one of the fetuses of a twin pregnancy died; the new regulations do not allow the dead fetus to be removed to save the living one or the woman; the doctors waited until the other fetus had died. Before this happened, the woman died from septic shock; her three children were orphaned. This time, the street protests were very few.

So who will write the history of the tears? For me, the exhibition at the MoMA is a depressing attempt to write the story of the lost battles for reproductive rights in Poland. The universalization of this topic is not uplifting. At this point, it is hard to be hopeful for change or expect public opinion to be mobilized.

*

Unseen. Stories of Warsaw Servants is an exhibition that opened at the Museum of Warsaw, not a contemporary art museum, but a city institution that mostly presents exhibitions connected with the history of Warsaw. The idea for the exhibition did not come from current political events but stems rather an interesting tendency present in historiography: the writing of the people’s history of Poland. Not history written from the perspective of masters but from the perspective of the oppressed, of which the women coming from villages to the cities to become a house workers used to be a significant group. The theme of the exhibition is female servants as invisible characters in the history of Warsaw. It is obviously rooted in the recently published books by Joanna Kuciel-Frydryszak and Alicja Urbanik-Kopeć. But the exhibition space also opens with readings from Piotr Laskowski’s excellent article on Jewish female servant and her autobiographies as opposed to “big” historical narratives. The reference to the historical research is clear in the next rooms of the exhibition. Therefore, the narrative of the exhibition is not directed from current events towards their historicization, but from recent historical breakthroughs towards contemporary debate.

[Exhibition view Who Will Write the History of Tears; photo by Sisi Cecylia]

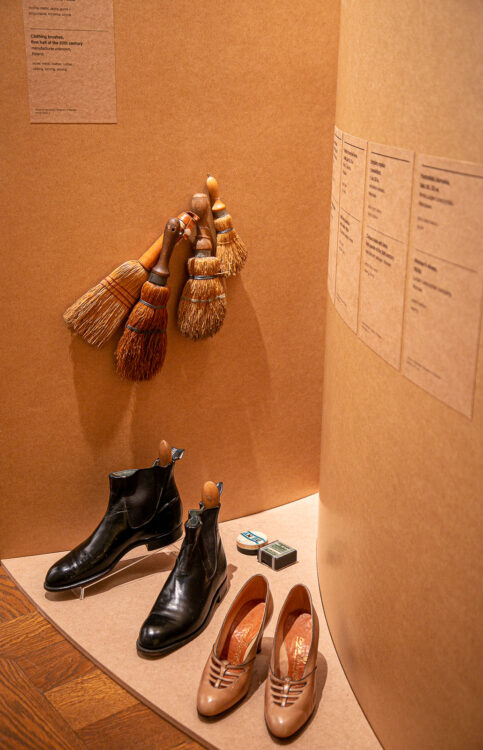

As mentioned before, the exhibition is very much a historical show, featuring objects and artifacts from the era – the interwar period and from Warsaw – defining them with numerous materials showing the context of the servants’ work. There is also the theme of the sexual exploitation of woman, but this is a side topic, with the domination of themes like poverty, the subordination of the servants’ private lives, and quite separate thematic sections such as “the maid as an ornament” and the organization of unions of servants.

[Exhibition view Unseen; photo by Tomasz Kaczor]

[Exhibition view Unseen; photo by Tomasz Kaczor]

Right next to the entrance to the exhibition space, in a display case, an interesting object that connects Warsaw and Buenos Aires can be seen. It is a book published in 1928 by a French criminal journalist, telling the story of one of the largest human trafficking organizations of the interwar period. Under the name Varsovia Jewish Mutual Aid Society (later known as Zvi Migdal), pimps were finding young women looking for a job as servants in Warsaw and sending them to brothels in Buenos Aires. As the curatorial text informs us, the criminal organization was crushed in 1930, after nearly four decades of activity.

[Exhibition view Unseen; photo by Tomasz Kaczor]

An advantage of the whole narrative of the exhibition is its clear setting in one place – Warsaw – and at one time – the interwar period. This keeps the perspective in check and explains the curatorial choices. But this historical clarity also helps to construct its relationship with other contexts, such as the above-mentioned geographical settings: Buenos Aires or the later epochs. The relationship with the present day is the theme of the last room of the exhibition. Here, contemporary artworks from different periods (since period of People’s Republic of Poland till the present day) have been quite freely connected with the topic of women’s labor. This is a way of pointing to the contemporary relevance of the subject and the various paths of its interpretation. The room is filled with sculptures, paintings, collages, photographs such as the one documenting the black protest slogan: “We refuse servitude at home and at work” (clearly referring to the female servants’ vocabulary). The main place in this room is occupied by the video that links the topic of the exhibition with the current situation of women coming to Poland from Ukraine. In the film, artist Katarzyna Swinarska interviews a woman from Ukraine, who used to take care of the artist’s very old grandmother. They role play a typical dialogue between the lady and the servant. One can see how similar the patterns of subordination of the life worker are.

[Exhibition view Unseen; photo by Tomasz Kaczor]

Although the idea of the show might be understood as the visualization of the current debates in the field of history, anthropology, and literature in Poland, not in terms of art exhibition (the role played by contemporary art is marginal; historical objects are not used for visual analysis) nevertheless, it constitutes a strong voice in contemporary debates about the status of women’s labor and life work in society. As a museum exhibition, it encourages a critical look at objects, collections and modes of history writing in art institutions in which life workers – crucial for reproduction – are almost completely unseen. As the story of female servants shows, it is hard to find their traces – even in pictures, documents or archives.

Despite these depressing findings, I leave the exhibition glad. It has meant a bright change of a narrative to me. An attempt to write history not in favor of the masters, but the oppressed. It gives hope that the history of women’s reproductive labor is beginning to be written. That people’s histories are changing the canons of storytelling, and that new ways of looking at the past are being sought. One cannot look at historical narratives any more without asking who washed the socks of the great men and women and took care of his/her children when he/she was writing the history.

By: Wiktoria Szczupacka