Women Artists and National Art Histories: the case of Andrée Moch in Argentina

Author: Georgina G. Gluzman

In Argentina, art history has been written as a local account. However, circulations have been crucial for the Argentine scene . This short text explores the connections between women artists and migration, by focusing on the case of Andrée Moch (1879-1953). Her status as a woman and outsider is at the origin of their negation in Argentine art history.

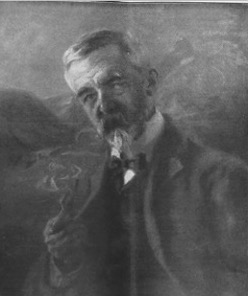

Andrée Moch (1879-1952) in her studio in Buenos Aires, in 1919.

The critical rewriting of art history is closely connected to the development of our own skills to go beyond traditional concepts. The discipline of art history is closely connected to national histories, identities, and power relations. Moch poses a problem within this construction where “center/periphery”, “national identity”, and “purity” are still largely present.

Andrée Moch was born in Paris to a well-to-do family. Her prosperous situation would come to an end when her father passed away. After this loss, Moch decided to train to become a professional artist, first in Bordeaux and then at the Parisian École des Beaux-Arts, which had recently fully opened its doors to women. She trained both as a painter and as a sculptor. In 1905 she exhibited a relief inspired by Roman art at the Salon des Artistes Français, with very little critical recognition. Her love of travelling and her desire to expand her professional horizons took her to England and Spain in the early years of the 20th century.

In 1907, Moch exhibited in Spain with success. The works the artist presented on that occasion have been lost. However, their subject matter is known: Moch exhibited several portraits and landscapes, painted in England and in Spain, including in the Basque Country. The titles of some works recall Spanish traditions and well-established topics of Spanish art.

After the Spanish sojourn, Moch decided to travel even further and embarked to Buenos Aires in 1908. She arrived with the vague prospect of receiving a commission to create a monument, in the hectic years before the celebration of the Centenary of the May Revolution in 1910, when several monuments to the “great men” of the Argentine history were erected.

Weeks after her arrival, she organized a solo show at the Galería Witcomb, which received mixed reviews. After waiting for months for the jury in charge of assessing her maquette to visit her at her studio, Moch did not secure the commission. But this extremely resourceful artist had already begun to plan her next moves. Her sojourn in the Basque Country helped her to establish links with the Basque community in Buenos Aires and soon after her arrival she became a collaborator for La Baskonia, the magazine of the Basque community in the city.

Andrée Moch (1879-1952), Una cumbre del Tandil, present whereabouts unknown.

The places and the history of Argentina, particularly of the city of Buenos Aires, replaced her old themes The porteño art market was eager to acquire the vibrant-colored paintings of familiar places of the city, as well as the landscapes she painted after travelling all around the country. Museums and other official institutions acquired several of her works, such as the large painting of the Tres de febrero park in Buenos Aires, currently at the Historical Museum of Buenos Aires.

Andrée Moch (1879-1952), Parque Tres de febrero, Palermo, 1922, oil on canvas, 220 x 305 cm, Museo Histórico de Buenos Aires “Cornelio Saavedra”.

In her life, Moch carefully recorded her experiences in memoirs and poems. The space she devoted to her many trips is a testimony of the relevance given to these experiences. Her writings enhance our knowledge on how gender and displacement intersect. This topic constitutes a central element of Moch’s memoirs: creative freedom is achieved through the displacement in space and in the joy of finding a new home away from one’s own birthplace.

In 1939, more than thirty years after her arrival, Moch published Andanzas de una artista, her 600-page autobiography. This remarkable book, the first of its kind written by a woman artist in Buenos Aires, announced from its very title the topic: the wanderings of a woman, from Europe to the Americas. Moch wrote: “These adventures are the history of my life. The things that followed took place in it. I must tell them”. The artist stressed the importance of writing her memories, as personal recollections contain “data not found in didactic books”, an unmistakable reference to the suppression of women artists and more widely of women from historical accounts.

Moch was explicitly expressing her willingness to add her own voice to the memory of her times. Her writings abound in detail concerning her walks through the streets of Buenos Aires. Moch is a flâneuse, paying attention to the city and its inhabitants as she walks or takes the tramway.

Though Moch always presented herself as a wanderer, even an outcast, she evidently encountered in Buenos Aires a large community that valued her work and finally settled. She embraced the city as one of her main sources of inspiration. While she did not abandon more traditional landscapes, the depiction of the hectic city of Buenos Aires became a key topic for her, both in her paintings and in her writings. Here, she was also able to experiment with sculpture, one of her preferred media. Moch found another very profitable activity: painting portraits, especially within the Basque community. A French-born artist, she was often regarded as a Basque in Argentina. The many portraits of members of this community that she made are a testimony of the circle that embraced her.

Andrée Moch (1879-1952), Florencio de Basaldúa, 1909, oil on canvas, present whereabouts unknown.

Teaching was a means of life for women artists, from which they obtained financial resources, but it was also a way of life, which enabled them to have an enormous impact on cultural circles. There were many women artists who supported themselves totally or partially thanks to teaching: in private classes in their workshops or in schools of different levels. Teaching was not merely an economic activity. They were nourished by the wishes of disciples to be educated alongside them. Their workshops were also a space of authority, which was often denied to them in other areas. Moch was acknowledged by literally hundreds of her students.

Moch’s gender was crucial to the construction of their artistic identities, not an obstacle as the first feminist art historians may have thought. The romance between Argentine elites and “all things French”, but specifically feminine artistry, had begun several decades before Moch arrived. In the late 19th century, the increasing modernization of women’s roles in Argentina was accompanied by a permanent reflection about women in other countries, a subject developed particularly in the periodical press. France was presented, from the 1850s on, as the most advanced nation in relation to the cause of women. This helped Moch to establish her reputation and to attract attention in art circles.

Andrée Moch has been doubly negated in traditional art histories in Argentina. Her double condition of woman and foreigner explains the absence of a relevant figure of her times.